Social stigma refers to negative attitudes and beliefs that motivate any group to fear, reject, avoid, and discriminate against another group of people. In one of the few studies to examine empirically the social perception of addictive disease, Shaffer (1987) found a clear distinction between the perception of biological and behavioral disorders. This issue of Addiction and the Humanities examines the results of Shaffer’s study in conjunction with a recent review of the literature on stigma and marginalization in relationship to psychoactive substance use (Room, 2005). This discussion examines factors that contribute to the ongoing moralization of alcohol and drug problems, which, in turn, contributes to the stigmatization and marginalization of people with addiction.

Shaffer recruited 96 individuals (44.8% male; 55.2% female) within a variety of community settings (e.g., schools, work places, and waiting areas). Participants responded to a prerecorded audio tape of 80 words or phrases and judged each using a Likert-type scale (i.e., definitely yes, probably yes, uncertain, probably no, and definitely no) in response to whether or not the word or phrase represented a disease. Shaffer then factor analyzed the data to obtain clusters of words that represented a homogeneous subset of variables (i.e., a group of items that had similar patterns of Likert scale scores).

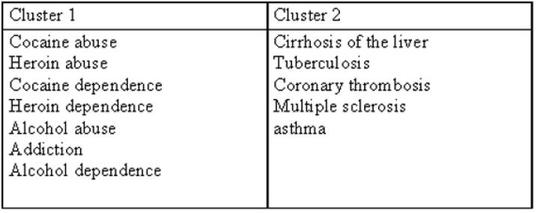

Shaffer’s results showed that individuals subjectively distinguished disease items that had a clear biological aspect to them (e.g., muscular dystrophy, cirrhosis of the liver, multiple sclerosis) compared to those disease items that reflected behavior patterns (e.g., cocaine abuse, heroin abuse, alcoholism). Table 1 summarizes the clusters or groups of items that factor analysis identified. Clearly participants did not perceive addiction-related behaviors (e.g., alcoholism, heroin dependence, or chemical dependence) as the same kind of disease as biologically based diseases (e.g., cirrhosis, tuberculosis, asthma, etc.).

Jungian-based therapy introduced ideas about the influence of the unconscious on both Pollock’s emotional troubles as well as his art. Jackson had trouble expressing his troubles verbally and often showed his work to aid the analysis (Frank, 1983, p. 30). This process revealed how art served a primary mode of communication for Pollock. The impact of Jungian-based therapy encouraged free association: this process ultimately resulted in Pollock’s drip or splatter method in the late forties for which Jackson became famous (Fineberg, 1995).

Table 1. Disease Clusters (adapted from Shaffer, 1987)

Room (2005) conducted a literature review to examine societal views about alcohol and drug problems and considered how these views affect individuals who are addicted to psychoactive substances. Consistent with Shaffer (1987), Room found ongoing social disapproval or stigma related to addiction. This circumstance was associated with de-prioritization of addiction within the healthcare system. Room identified three related elements of addiction that might influence the degree of social disapproval and moralization associated with behavioral addictions: unpredictability; losing control; and cultural context. First, intoxication is associated with unpredictability (e.g., abandoning the norm, or sobriety; and losing inhibitions); this might cause anxiety for those who come into contact with an intoxicated person. Second, Room suggests that society views those who lose personal control to a substance, which he describes as being characterized by society as a “disease of the will,” as blameworthy. Third, the cultural context within which the substance use occurs will influence the extent of social stigma (e.g., a Muslim drinking alcohol or a pregnant woman drinking in the U.S.) and the mechanisms within a society that lead to stigma and marginalization.

Room also identified three main processes of social control that might be a source of ongoing stigmatization and marginalization. First, interactions with friends and family members serve as a powerful social control, which can provoke isolation of a person with addiction. Second, some decisions by social agents and agencies, which tend to focus their attention on the most severe or problematic individuals (e.g., methadone clinics or needle exchanges), might inadvertently lead to more marginalization if their efforts fail to effectively reintegrate people with addiction into society. Finally, some policy decisions at the local and national level might increase stigmatization and marginalization. For example, a federal U.S. law that requires a family to be evicted from public housing if any member of the family is associated with drug dealing or, on a local level, the Rockefeller drug laws in N.Y. that require extended prison terms for the possession or sale of relatively small amounts of drugs.

As both Shaffer and Room have shown, the social perception of drug and alcohol problems distinguish addiction from other deviant behavior patterns; these public perceptions sustain the negative view that addiction results from personal choice and immoral values. These views often seep into various aspects of life. For example, consider how the media portrays addiction, how matters of addiction are taught in school, how families discuss people with addiction, and how the legal and medical systems deal with people suffering with addiction.

However, although some observers might argue that moralization and marginalization are effective ways of curbing addiction, theses approaches have not worked optimally. Despite attempts to portray addiction as a disease, Shaffer has shown that the public still views addiction as something different from biologically based diseases, despite their willingness to call it a disease. To help people with addiction, it is crucial to effect change within the same channels that perpetuate stigmatization of addiction (e.g., media, legal system, medical system). Both researchers and clinicians should make energetic efforts to lessen the degree of moralization placed upon substance misuse and addiction. Therefore, future efforts will need to focus on improving methods of treatment and community reintegration. Further, these efforts will have to shift the social perception of addiction from a one dimensional “disease of the will” or a “disease of the body” to a multidimensional illness with all of the attendant biopsychosocial factors that typically accompany the presence of sickness.

What do you think? Comments can be addressed to Juan Molina.

References

Room, R. (2005). Stigma, social inequality and alcohol and drug use. Drug and Alcohol Review, 24, 143-155.

Shaffer, H. J. (1987). The Epistemology of "Addictive Disease": The Lincoln-Douglas Debate. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 4, 103-113.