The prohibition of beverage alcohol in the United States between 1919 and 1933 and its success or failure continues to be a topic of scientific research and public debate. A recent article in the American Journal of Public Health provides an interesting contribution to this topic from the perspective of a historian (Blocker, 2006). Moreover, it raises interesting questions: Could alcohol prohibition return? Can prohibitions of any kind and in any form be viable public health options?

The article begins with an overview of the historical processes leading to the Prohibition Act and its repeal. Next, he summarizes expected and unexpected effects of the Prohibition Act. The author concludes that, as expected, prohibition actually did lower per capita alcohol consumption. However, not as expected, women emerged as a new group of public drinkers.

Blocker goes on to derive lessons for today’s prohibitions on tobacco, illicit drugs, and guns. His view is that prohibitions can be a public health option, but effectiveness might vary depending on the type of banned object or activity and, most importantly, depending on historical context. “Historical context” means that prohibitions could work in one place but not another, in one time but not another, and in one population but not another (Tyrrell, 1997). Blocker argues that for prohibitions to succeed, the aim should not be a legislation of morals and not a regulation of economy, but should be a concern for public health. He argues that prohibitions can succeed when widespread public consensus is behind a prohibition and its enforcement. For example, regarding passive smoking laws or illicit drugs, at least partial prohibitions are in place today and are driven by strong public support. Further, the author explains that qualities of the banned articles (e.g., the conditions of production, the value to an illicit trade, or the ability to conceal the article) will affect the success of prohibitions. Health and social costs but also potential benefits of prohibitions and effects on both the individual and the society at large are important to consider.

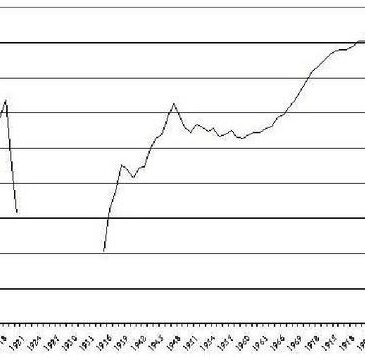

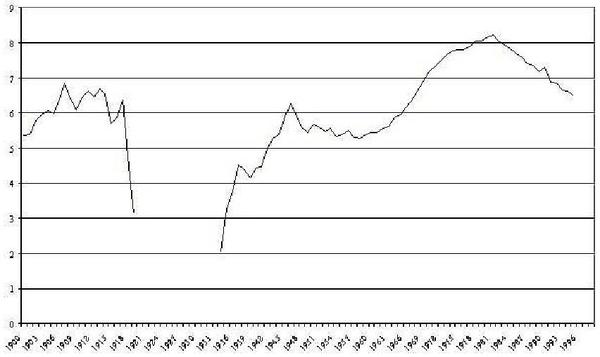

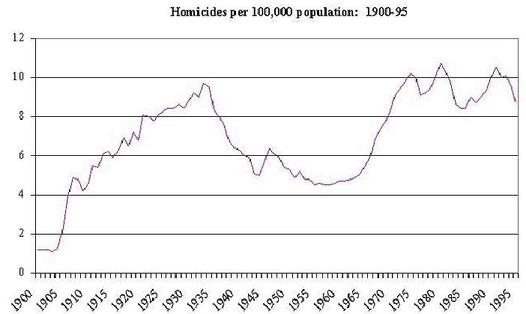

The article has some limitations because of its editorial style. It neither reports an empirical study nor provides a comprehensive review of research findings about the effects of the Prohibition Act. Rather, it presents a narrative summary of selected arguments to support the author’s opinion. While this is a justifiable approach, it is also open to certain biases. For example, the author argues that alcohol consumption decreased during the prohibition but he does not cite any empirical evidence to support this claim. Also, he fails to balance this claim by discussing that crime rates might have increased during the prohibition (see Figure). From Blocker’s perspective, changes in historical context could result in new and renewed legislated prohibitions, which he considers to be public health innovations.

Figure. Alcohol consumption may have decreased while crime rates may have increased during the prohibition in the United States between 1919 and 1933 (adapted from Miron, 2001). Click image to enlarge.

—Anja Schumann

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

References

Blocker, J. S. (2006). Did prohibition really work? Alcohol prohibition as a public health innovation. American Journal of Public Health, 96(2), 233-243.

Miron, J. (2001). Alcohol Prohibition. In R. Whaples (Ed.), EH.Net Encyclopedia: http://eh.net/encyclopedia/article/miron.prohibition.alcohol. Website accessed Nov 22, 2006.

Tyrrell, I. (1997). The US prohibition experiment: myths, history and implications. Addiction, 92(11), 1405-1409.