A recent study by Tavares, Zilberman, Beites, & Gentil, (2001) suggests that there are differences in the progression of disordered gambling behavior between men and women. Thirty-nine women and 38 men seeking treatment at a Brazilian treatment facility for pathological gambling were screened according to both DSM-IV (APA, 1994) and the South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS; Lesieur & Blume, 1987). Participants were recruited by advertisement and completed a brief questionnaire that collected demographic information and asked questions about personal gambling experiences. This WAGER focuses primarily on analyses of gender differences in the duration of specific stages of gambling (social gambling, intense gambling, problem gambling).

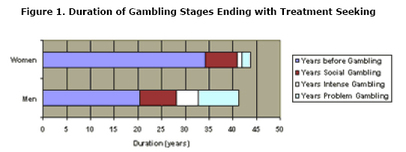

Treatment seeking women started gambling significantly later in life than did treatment seeking men (mean age 34.2 years for women vs. 20.4 years for men, p<0.01). There was no significant difference in the duration of social gambling for women (6.7 years) and men (7.7 years). After adjusting for marital and job status, women had significantly shorter periods of intense gambling (1.0 year) than men (4.6 years, p<0.02), and a significantly shorter duration of problem gambling (1.8 years) than men (8.6 years, p<0.001). No differences were observed for the age at which women and men first sought treatment (44.7 years vs. 42.3 years, respectively). Figure 1 illustrates the differences in gambling course observed for men and women.

Figure 1 illustrates that women started gambling later in life than men, but engaged in social gambling for a similar duration. Women then escalated through intense gambling to problem gambling at a much faster rate than men. It is interesting that despite their differing trajectories, men and women tended to seek treatment at roughly the same point in their lives. Thus, on average men maintained problem gambling levels for longer periods of time than women.

The Tavares et al. study might be limited in several ways. It was conducted using a small sample in Brazil and only explored individuals who sought treatment. This makes the stability of the reported effects uncertain. Further, it is questionable whether we can generalize these findings to other populations or community samples. Although not necessarily a limitation, it is important to note that the descriptive nature of the research and the limited amount of patient information provided preclude investigation into the cause(s) of the observed progressive differences. Related work has found that among problem gamblers, women are more likely than men to tend to seek treatment for personal issues (e.g., intrapersonal functioning), rather than non-personal issues (e.g., finances) (Crisp, Thomas, Jackson, Thomason, Smith, Borrell, Ho, & Holt, 2000). Perhaps this discrepancy in focus contributes to the divergence in progression between men and women.

The research of Tavares et al. advises us to pay more attention to variations in gambling progression across individuals. Their work highlights these potential differences, encouraging clinicians to take careful histories and tailor both treatment and prevention strategies to the unique needs of each gambler.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV), fourth edition. Washington, DC.

Crisp, B. R., Thomas, S. A., Jackson, A. C., Thomason, N., Smith, S., Borrell, J., Ho, W., & Holt, T. A. (2000). Sex differences in the treatment needs and outcomes of problem gamblers. Research on Social Work Practice, 10(2), 229-242.

Lesieur, H. R. & Blume, S. B. (1987). The South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS): A new instrument for the identification of pathological gamblers. American Journal of Psychiatry, 144, 1184-1188.

Tavares, H., Zilberman, M. L., Beites, F. J., & Gentil, V. (2001). Gender differences in gambling progression. Journal of Gambling Studies, 17(2), 151-159.

The WAGER is a public education project of the Division on Addictions at Harvard Medical

School. It is funded, in part, by the National Center for Responsible Gaming, the

Massachusetts Department of Public Health, the Addiction Technology Transfer Center of

New England, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and the

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment.