ASHES, Vol. 20(4) – Identification of shared and unique risk factors for cigarette and e-cigarette use among adolescents

Despite declining tobacco use worldwide, harms from tobacco remain a major public health concern. The COVID-19 pandemic put additional strain on public health, as health care needs increased and economic resources tightened. The popularity of e-cigarettes among young people complicates public health efforts, as it is unclear whether cigarette smoking and e-cigarette use share risk factors. This is an important delineation, as interventions geared towards cigarette smoking prevention/cessation may not be as effective in younger generations who favor e-cigarettes. This week, ASHES reviews a study by Dèsirée Vidaña-Pérez and colleagues that explored the factors that influenced cigarette and e-cigarette use among Guatemalan adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic.

What was the research question?

What factors were related to adolescent nicotine use before and during the COVID-19 pandemic?

What did the researchers do?

The authors surveyed students from 10 schools in Guatemala City (n = 2,123) in an open cohort using adapted versions of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health survey and the International Tobacco Control Youth survey before the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants indicated their current smoking/vaping status, susceptibility1 to smoking/vaping, frequency of exposure to advertisements for nicotine products, frequency of convenience store exposure, smoking/vaping habits of family and friends, alcohol and marijuana use, perceived harm from tobacco products, and sociodemographic characteristics. Students from nine of the same ten schools (n = 1,606) answered the same questions one year later (during the pandemic). The authors assessed participants’ cigarette use and e-cigarette use, and factors that might have influenced those changes, at both waves using logistic regression analysis.

What did they find?

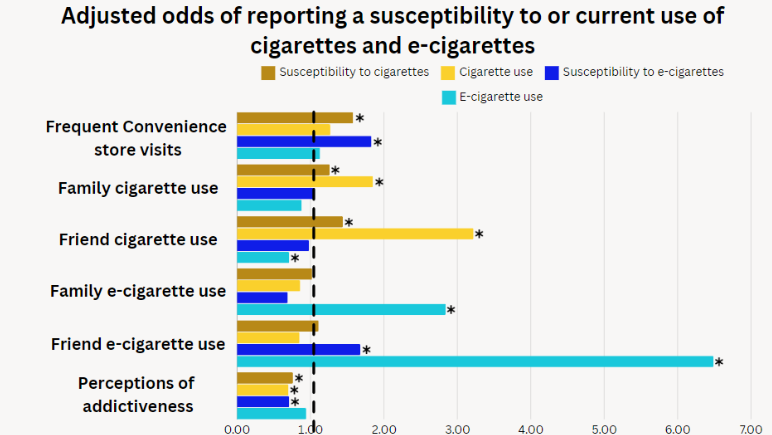

When participants were surveyed during the pandemic, they reported lower cigarette and e-cigarette use, convenience store/ad exposure, and use of cigarettes and e-cigarettes by family and friends compared to pre-pandemic. After combining both waves into a single time point, the researchers found that those who made frequent visits to the convenience store described themselves as more susceptible to both smoking and vaping, but they were not more likely to vape or smoke (see Figure). Use of cigarettes and e-cigarettes by family and friends was also related to participants’ own cigarette/e-cigarette use. Interestingly, participants were more likely to smoke or use e-cigarettes if their family or friends did so, suggesting social contagion effects. Finally, those who perceived cigarettes or e-cigarettes to be more addictive were generally less likely to describe themselves as susceptible to these behaviors or engage in these behaviors, with the exception of e-cigarette use, which was unrelated to beliefs about addictiveness.

Figure. Adjusted odds ratios of study outcomes. Odds ratios greater than 1 indicate greater odds, while odds ratios less than 1 indicate lower odds. As an example, participants who indicated that they had friends who use e-cigarettes had 6.49 times (i.e., greater) odds of being a current e-cigarette user while those who perceived smoking to be addictive had 0.70 (i.e., lower) odds of being a current smoker. *indicates a statistically significant relationship. Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

This study found that many of the risk/protective factors for cigarette use also apply to e-cigarettes. This is important because it suggests that current smoking prevention/cessation programs may apply to e-cigarettes as well. Current anti-cigarette programs should incorporate evidence-based language focusing on e-cigarettes in light of these findings. The results also emphasize the importance of social networks in smoking/vaping initiation. Interventions focused on avoiding and combating peer pressure may prove especially effective in reducing adolescent tobacco use.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations in this study?

This study is limited by generalizability issues on two fronts. First, there is an issue of timing. Because follow-up occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is unclear how accurately it reflects the current environment, as lockdowns and other temporary policies have largely been lifted. Further, it is unclear whether these results apply to youth in other locations with different smoking/e-cigarette norms and regulations.

For more information:

Individuals who are concerned about their vaping and want to learn more may benefit from visiting the CDC webpage on vaping. Others who seek to cease their nicotine use may benefit from visiting the Truth Initiative. Additional resources can be found at the BASIS Addiction Resources page.

—John Slabczynski

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

________________

1. Susceptibility to smoking/vaping was defined as responding with anything other than “definitely not” to one of the below two questions:

1. “Do you think at any time during the next 12 months, you will smoke/use an e-cigarette?

2. “If one of your best friends offered you a [cigarette/e-cigarette], would you smoke/use it?”