The DRAM, Vol. 18(2) – ACEs and alcohol use: Predictors of intimate partner violence among Black men

No one can control the types of things we are exposed to as children; however, these experiences impact the way we live our lives as adults. People living with the lasting effects of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) are more likely to perpetrate intimate partner violence (IPV). Turning to alcohol and other drugs to cope with past trauma itself increases the risk of perpetrating IPV. As a result, the association between ACEs and perpetrating IPV might be especially strong among men who drink heavily. This week, The DRAM reviews a study by Kerry A. Lee and colleagues that examined ACEs, alcohol use in adulthood, and their effects on IPV perpetration among Black men in the United States, a historically understudied group.

What was the research question?

How do ACEs and adult drinking, when considered in combination, predict IPV perpetration among Black men?

What did the researchers do?

The researchers analyzed data from Wave 2 of the National Epidemiological Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). This study included a sample of 1,127 non-Hispanic, Black men who reported being in an intimate relationship with a woman and used alcohol in the past year. The researchers assessed IPV in the past two months (e.g., slapping, weapon-brandishing, injuring severely enough to require medical care). They used ten items to assess ACEs. Questions related to alcohol use were taken from the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disability Interview Schedule DSM-IV (AUDAIS-IV), including the number of standard drinks per day. The researchers conducted bivariate and multivariate analyses to estimate the effects of ACEs and alcohol consumption on IPV.

What did they find?

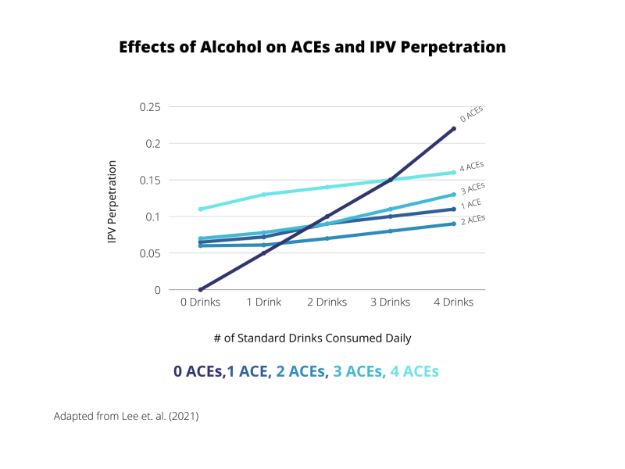

Nearly three-quarters of participants (72.2%) were exposed to adversities in childhood, with 20.4% reporting four or more ACEs. The most common ACEs were emotional abuse, physical abuse, and physical neglect. Men who experienced these ACEs had higher rates of IPV perpetration compared to men without these experiences; for instance, 10.7% of men who experienced emotional abuse reported perpetrating IPV, compared to 3.9% of men without a history of emotional abuse. Several ACEs were also linked with heavier drinking, which in turn was linked with IPV perpetration. Lastly, ACEs and alcohol use interacted to predict IPV in a surprising way. Among men with no ACEs, heavier drinking predicted higher odds of perpetrating IPV, but among men with ACEs, the relationship between drinking and perpetrating IPV was relatively flat (see Figure).

Figure. The relationship among alcohol, ACEs, and IPV perpetration. The x-axis reflects participants’ reported daily drinks as indicated by Wave 2 of NESARC data. Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

IPV perpetration by Black men is an understudied topic. This is the first known study to explore the role of ACEs and adult drinking on IPV perpetration among Black men. The findings suggest that alcohol use particularly increases the likelihood of perpetrating IPV among men with no ACEs. The authors speculate that men who did not experience the chronic, toxic stress of ACEs became more susceptible to the disinhibiting effects of alcohol, causing them to be more aggressive when under the influence. In other words, the long-term ”wear and tear” of traumatic experiences on the developing brain and body could paradoxically blunt some of the effects of alcohol in adulthood. With this knowledge in mind, addressing the needs of Black men at high risk of perpetrating IPV should come from community action such as increased social supports and policy change such as anti-violence and community development initiatives to lighten the load of government agencies (e.g., law enforcement, social services). These findings will hopefully urge other researchers to further investigate the role of ACEs and substance use on IPV with a specific focus on Black men.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations in this study?

Black men of different ethnicities, classes, and cultures might have experiences with regard to ACEs, drinking, and IPV. The samples were too small to allow for subgroup analyses, and the NESARC survey did not include the sorts of items necessary for the researchers to explore culturally specific factors. Lastly, the retrospective nature of the ACEs questions can be prone to bias, and the type of cross-sectional data used does not allow for causality to be determined, especially related to alcohol use and IPV.

For more information:

The National Coalition Against Domestic Violence has resources for people who are affected by intimate partner violence or know of someone who is affected. The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism also has tips and resources for people struggling with problem drinking. For additional drinking self-help tools, please visit our Addiction Resources page.

— Nakita Sconsoni, MSW

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.