The DRAM, Vol. 16(2) – Super Bowl swigs: Applying social practice theory to alcohol consumption

Today’s review is part of our month-long Special Series on Theories of Addiction. During this Special Series, The BASIS features recent publications that investigate the application of theories and models to addiction science.

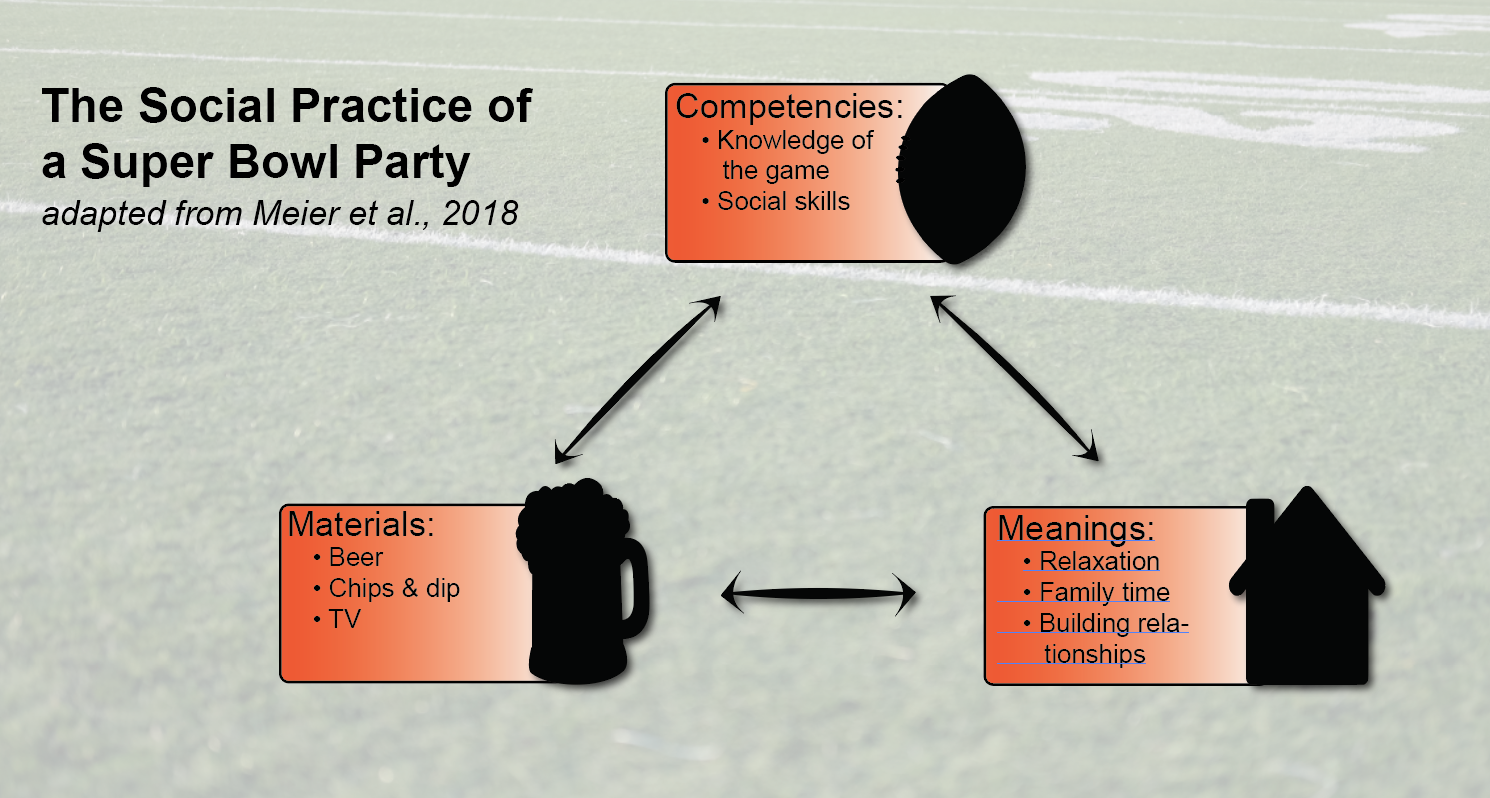

Some things just go hand in hand: peanut butter and jelly, birthdays and cake, football and beer. In fact, it’s very difficult to imagine attending a Super Bowl party that has no beer. But why is that? Few behaviors can be understood in isolation and alcohol use at a Super Bowl party is no exception. One proposed method to better understand the complexity of human behavior is to shift the focus from the individual behavior to the “practice” itself. A practice can be broken down into three elements: competencies, materials and meanings (see figure).

Figure. Social practice of a Super Bowl Party. Materials, skill/competency and meaning all play an important and intertwined role in a practice. Click image to enlarge.

This social practice theory (SPT) approach emphasizes the importance of looking at the routinized nature of human behavior and how it can be influenced by the context and social landscape within which it occurs. For example, we expect that the practice of attending a Super Bowl party will include certain things like raucous cheering, discussions of the best commercials, seven layer dip – and of course, drinking. In fact, drinking and partying is so integral to this practice that a projected 17.5 million workers will call out of work the Monday following the Super Bowl. That’s a whole lot of lost productivity nationwide! SPT might provide insights into why we drink on occasions like these or even at all. The approach aims to shift the focus from the individual human performer of the behavior to the behavior itself (a practice) and the context in which it occurs. Additionally, it examines how practices relate to each other (e.g., drinking while watching sports), hold each other in place (e.g., a glass of wine while cooking), or compete for time (e.g., watching sports vs. cleaning the house). This week, as part of our Special Series on theories of addiction, The DRAM reviews a paper by Petra Meier and colleagues that advocates for approaching alcohol research through a SPT lens, with a focus on (1) the current state of the research and (2) what social practice theory has to offer.

Current state of alcohol research

- Drinking alcohol is often viewed as an individual behavior. Studies often focus on the amount consumed or individual risk factors for heavy drinking while overlooking location, context, purpose, and timing of the behavior.

- Alcohol research is influenced heavily by theories of behavior. These theories often assume participants are autonomous, well-informed, and rational decision makers about their drinking behavior.

- Many interventions based on behavioral theories have struggled to implement real change or have not demonstrated consistent replicability across groups.

What social practice theory has to offer

- Benefit 1: Studying drinking practices allows researchers and policymakers to understand how drinking fits in with other parts of the drinkers’ lives, like family and work. Importantly, this approach can lead to understanding how disruption of one practice can affect a seemingly unrelated practice.

Example: Could changing the time or date of the Super Bowl cause less drinking and drinking-related harm? Maybe people drink more at a January Super Bowl because they’re inside huddled against the cold. - Benefit 2: Practice-based approaches allow researchers to differentiate the effects and outcomes of alcohol in different contexts. Measuring the volume of alcohol consumption alone is often not sufficient to predict harm.

Example: Is there a higher incidence of DUIs when fans watch the Super Bowl at a bar or at a friend’s house? Maybe friends encourage you to stay at your house until you’re sober. - Benefit 3: Practice-based approaches allow researchers to differentiate the effects and outcomes of alcohol use in different communities to develop uniquely tailored interventions.

Example: Do poorer communities have fewer safe transportation options, and, if so, does this increase the likelihood of DUIs after Super Bowl parties? Introducing public transportation in relatively poor communities might have a significantly greater impact than in a neighborhood where residents can afford taxis/rideshares/rides from friends.

What are the limitations of social practice theory?

Some argue that social practice theory doesn’t go far enough in shifting focus away from the individual. Let’s go back to the example of drinking while watching a sporting event. SPT allows researchers to explore the practices related to this, like drinking more because alcohol is available in the minifridge next to the couch or as part of an event identified as a chance to relax and let loose with friends. Suzanne Fraser argues that the utility of SPT becomes less clear when attempting to design practice-based interventions. A practice-based intervention for drinking during the Super Bowl might be to encourage throwing “dry” Super Bowl parties. Fraser notes that these types of interventions still require individual actions and choices and don’t focus enough on institutional issues, such as certain aspects of American sports culture that pair substances and sports at both the spectator and player level from an early age. As with most theories, it is important to remember that while social practice theory has its benefits, it is a single approach and likely not the solution to all of the problems present in alcohol research. Models that combine the strengths of multiple approaches and methods have the greatest chance of providing a comprehensive picture of addiction and providing insight for effective treatments/preventative measures.

For more information:

The National Institute for Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism has tips and resources for people struggling with problem drinking. For drinking self-help tools, please visit The BASIS Addiction Resources page.

— Alex LaRaja

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.