The DRAM, Vol. 13(13) – “Please drink responsibly.” So many questions, so few answers.

We have all seen messages to “drink responsibly,” whether on television, online, on billboards, or in other forms of media. But are these messages actually effective in helping people drink responsibly? And what do we mean by responsible drinking? Responsible drinking for a college student might be very different than responsible drinking for someone struggling with a 10-year alcohol use disorder. With these questions in mind, Antony Moss and Ian Albery conducted a research review to examine the existing research on the effectiveness of responsible drinking messages. This week, The DRAM reviews their study.

What was the research question?

What research exists about the effectiveness of responsible drinking messages?

What did the researchers do?

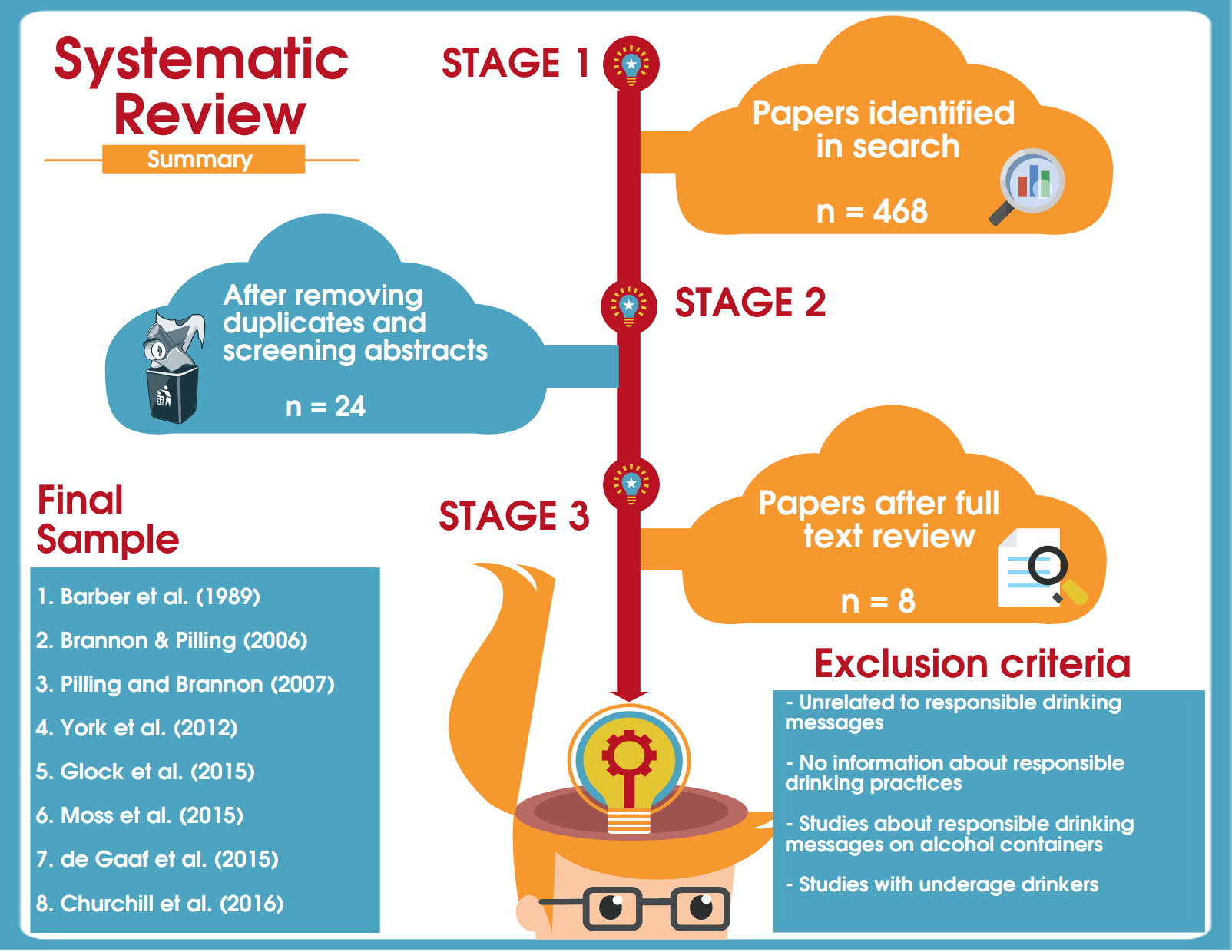

The researchers conducted a systematic review of the literature. They used variety of search terms (e.g. responsible drinking, alcohol misuse, mass media) to extract articles from three popular databases: PsycINFO, MEDLINE, and Google Scholar. They included studies that examined effects on attitudes towards alcohol or the responsible drinking message itself, alcohol-related risk perceptions, intentions to drink, and actual alcohol intake. They excluded irrelevant studies, studies of interventions which did not contain any message regarding responsible drinking, studies that evaluated the effectiveness of messages placed on alcohol containers related to unit contents, and studies involving underage drinkers (see Figure).

What did they find?

The researchers found that only 8 studies met their search criteria, and each study in the final sample varied in the way the responsible drinking messages were delivered and what they said, making statistical comparison of the studies unfeasible. Four studies examined the effectiveness of these messages on alcohol intake (Barber et al. (1989), Churchill et al. (2016), de Graaf et al. (2015), and Moss et al. (2015)), and found varied results. Whereas Moss et al. (2015) found that exposure to responsible drinking messages actually increased alcohol consumption, de Graff et al. (2015) found no such evidence. Barber et al. (1989) found that these messages were effective in decreasing consumption, but only when participants were notified about the advertising campaign ahead of time by mail. Churchill et al. (2016) found that a specific combination of message elements reduced alcohol consumption in the short term, but only for a subset of participants. The other four studies each addressed different outcomes, such as participants’ implicit associations about drinking.

Figure. Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

The scarcity of research about responsible drinking messages is somewhat surprising due to the money, time and effort public health organizations and industry groups have put into creating these campaigns. The lack of evaluation of responsible drinking messages leaves their effectiveness unknown, and the definition of responsible drinking remains unclear. Especially since there is some evidence that responsible drinking messages can have iatrogenic effects, public health institutions and industry groups have a responsibility to evaluate the effectiveness and outcomes of these messages.

Every study has limitations. What were the limitations in this study?

This study was primarily limited by the lack of available research. Researchers were also limited by their searching strategy. Other databases (i.e. PubMed or ProQuest) and search terms (i.e. “messages” or “advertisement”) might have provided additional studies for review. By not providing a clear definition of responsible drinking to work from, researchers may have excluded studies from their sample that would have added to the evidence about the effectiveness of responsible drinking messages.

For more information:

If you or a loved one is experiencing problems with alcohol, please click here.

Links to the papers in the final sample:

- Barber et al. (1989); 2. Brannon and Pilling (2006); 3. Pilling and Brannon (2007); 4. York et al. (2012); 5. Glock et al. (2015); 6. Churchill et al. (2016); 7. de Graaf et al. (2015); and 8. Moss et al. (2015);

— Alec Conte

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.