ASHES, Vol. 13(12) – Are cigarette prices and smoking bans effective levers for change?

Policymakers and advocates often argue that increasing the “cost” of smoking – whether in the form of an increase in cigarette price, or in the form of the added inconvenience for a smoker to step outside the bar/restaurant — causes individuals to smoke less. This week the ASHES reviews a study conducted by Dr. Amy H. Auchincloss and colleagues that followed individuals over time to see how these policy levers were associated with their smoking behavior.

What is the research question?

Are changes in local cigarette prices and/or smoking bans at bars/restaurants associated with changes in smoking behavior?

What did the researchers do?

From 2001 to 2012, the researchers followed 632 smokers from seven different metropolitan areas across the country, who were between ages 44-84 and free of cardiovascular disease when the study began. Using inflation-adjusted neighborhood cigarette prices and bar/restaurant smoking ban policies, they identified changes in these policies over time[1] and looked at the corresponding association with smoking behavior. Specifically, they were interested in the change in current smoking behavior, intensity of smoking, and the likelihood to stop or relapse smoking. The researchers used Poisson and Linear fixed-effect models to test associations between prices/policies and smoking behaviors.

What did they find?

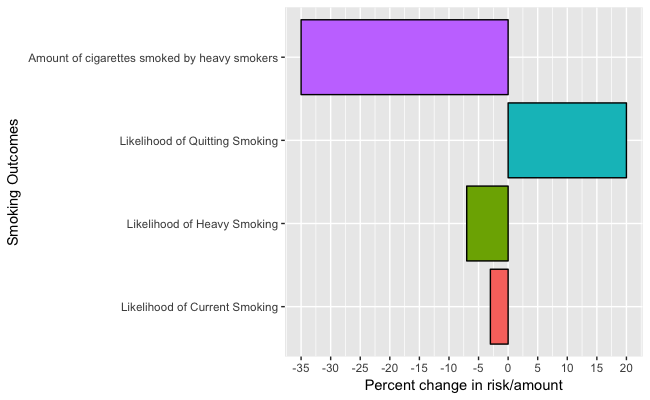

The authors found that a $1 increase in local cigarette prices was strongly associated with reduced risk of heavy smoking (7% decrease) and higher likelihood of smoking cessation (20% increase). Among heavy smokers at the start of the study period, the authors found a 35% reduction in the average number of cigarettes smoked per day per $1 increase – another strong association. The association between $1 increase in price and current smoking was relatively weak (3% reduction). The change in bar and restaurant smoking bans, on the other hand, had no association with smoking behavior.

Figure. The association between $1 increase in cigarette prices and smoking outcomes. Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

Given the considerable individual and public health costs associated with smoking, government interventions to dis-incentivize smoking behavior are often advocated. However, from a policy perspective, it is important to know what levers tend to work (and which ones don’t) in bringing about behavioral change. The study provides evidence showing that while increasing cigarette prices are effective in changing smoking behavior (particularly among heavy smokers), there is no evidence to suggest that bans in smoking at bars/restaurants work. These results are important and timely in the U.S., where such legislations are frequently introduced at various levels of government (for example, some federal lawmakers are currently proposing significant tax reductions for wine, liquor, and beer).

Every study has limitations. What about this one?

To measure cigarette prices, the authors used data from chain grocery and drug stores. If the data for the prices had included other venues from which individuals buy cigarettes, a better and more representative picture of spending would have emerged. Further, the outcomes included in the study relied on individuals reporting about their smoking behavior – to the extent that they don’t remember about their smoking behavior correctly, or don’t want to reveal their smoking habits to the researcher, the measurements of the outcome will be affected.

For more information:

Individuals who are concerned about their own smoking or vaping can find resources to help them quit at smokefree.org. Others struggling with their substance use more generally may benefit from using SAMHSA’s National Helpline. For additional tools, please visit the BASIS Addiction Resources page.

— Pradeep Singh

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

________________

[1] The authors used data from American Non-Smokers Rights Foundation (ANRF) Local Ordinance Database. Participants were categorized as having a smoking ban exposure if their census block group of residence had a legislation prohibiting smoking in restaurants and bars.