ASHES, Vol. 13(8) – Daughters of mothers who smoke: Are they more likely to smoke during their own pregnancies?

Editor’s note: Ms. Julia Peterson, an undergraduate student at Oberlin College, wrote the following research review. Ms. Peterson is completing the Division on Addiction’s Summer Research Mentorship program.

Children of mothers who smoke during pregnancy are at risk for a variety of adverse health outcomes, and are more likely than others to smoke and become dependent on nicotine as adults. However, as of 2013, an estimated 9% of women in the United States still smoked during pregnancy. When studying the population of mothers who smoke during pregnancy, it is important to consider intergenerational effects – that is, are daughters of mothers who smoke during pregnancy more likely than others to smoke during their own pregnancies? This week, ASHES reviews a study by Collette Ncube and Beth Mueller examining the relationship between fetal exposure to maternal smoking and daughters’ own smoking behavior during pregnancy in a large cohort of mothers and daughters.

What is the research question?

What is the risk of smoking during pregnancy among women whose mothers smoked during pregnancy, compared to women whose mothers did not smoke during pregnancy?

What did the researchers do?

The authors analyzed the birth records of 64,112 pairs of mothers and daughters who delivered a baby in Washington State from 1984-96 (mothers) and 1996-2013 (daughters). These birth records include information about maternal smoking. The authors examined the association between daughters’ prenatal smoking and mothers’ prenatal smoking. They also examined whether this association was affected by race, age, marital status, trimester of prenatal care initiation, number of prior births and pregnancies, daughters’ birth year, or daughters’ educational attainment.

What did they find?

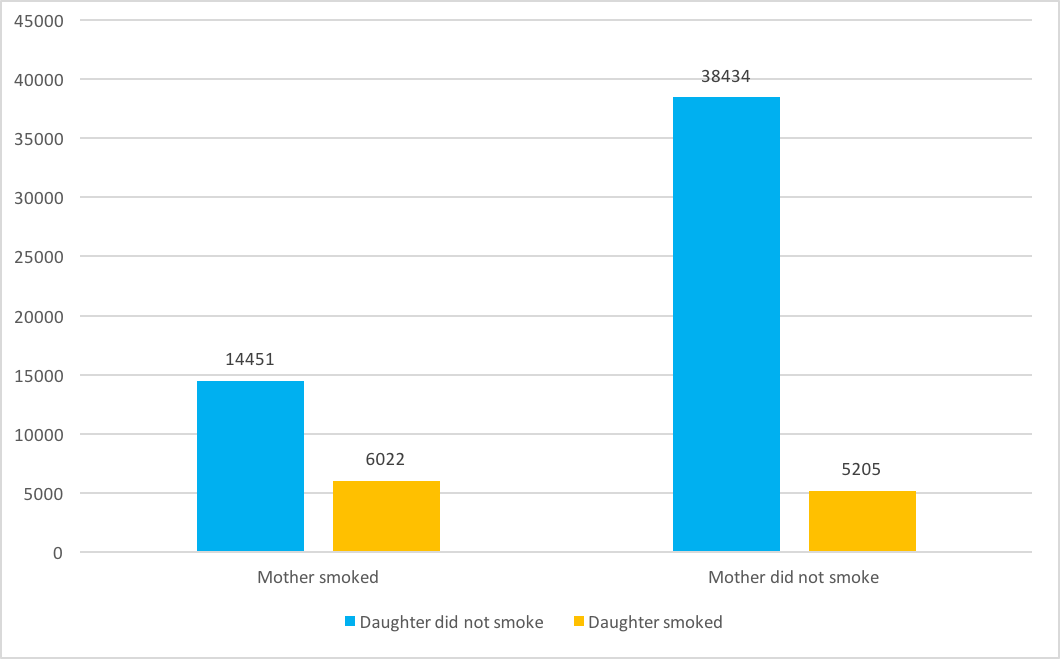

Daughters of mothers who smoked during pregnancy were more likely than other pregnant women to smoke during their own pregnancies (see Figure). Exposure to smoking in utero was still a risk factor for smoking during one’s own pregnancy even when researchers controlled for the year the daughter delivered, her marital status and educational attainment, and the mother’s race and ethnicity.

Figure. Prenatal smoking status of daughters born in Washington State, delivering 1996-2013, by their mother’s prenatal smoking status. Adapted from Ncube and Mueller (2016). Click image to enlarge.

Figure. Prenatal smoking status of daughters born in Washington State, delivering 1996-2013, by their mother’s prenatal smoking status. Adapted from Ncube and Mueller (2016). Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

The results of this study demonstrate that daughters of mothers who smoked during pregnancy are more likely to smoke during their own pregnancies. Identifying this risk factor is the first step to intervening in this cycle of intergenerational smoking, and can help healthcare providers identify at-risk patients.

Every study has limitations. What about this one?

This study used self-reported data, meaning that participants could have misreported their smoking behavior. Furthermore, because these data were collected only from birth records, this study can’t draw conclusions about whether prenatal exposure to smoking or exposure throughout childhood (or a combination of the two) leads to the associations between mothers’ and daughters’ smoking behavior.

For more information:

Individuals who are concerned about their own smoking or vaping can find resources to help them quit at smokefree.org. Others struggling with their substance use more generally may benefit from using SAMHSA’s National Helpline. For additional tools, please visit the BASIS Addiction Resources page.

— Julia Peterson

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.