The DRAM, Vol. 13(8) – Treating alcohol use disorder with motivational interviewing in active-duty army soldiers

Over time, more active duty soldiers have reported heavy alcohol use and prescription drug misuse. Some of these soldiers will require professional treatment. Even though treatment options exist, a very small number of soldiers actually receive treatment for substance use problems. Many soldiers drop out of mental health treatment early, either because they feel they can handle their problems on their own, feel they don’t have enough time for treatment, or experience stigma. Therefore, brief interventions might be especially helpful for this population This week, the DRAM reviews a study by Denise Walker and her colleagues that evaluates the use of a brief intervention—motivational interviewing with feedback—to treat alcohol use disorder in active-duty soldiers.

What was the research question?

How does a motivational interviewing with feedback session impact alcohol use behavior compared to a general education session in active US soldiers?

What did the researchers do?

The researchers recruited 290 active duty soldiers with alcohol or other substance use disorders into their study using different kinds of print media and in-person outreach.[1] Of the 290 eligible soldiers, 242 enrolled in the study and were randomly assigned to one of two treatment groups: Intervention or Education. The Intervention group received one session of motivational interviewing with feedback (MIF) over the phone, and the Education group received one educational session about substance use over the phone. Soldiers completed baseline, 3 month follow-up, and 6 month follow-up questionnaires about drinking, substance use, consequences, and treatment-seeking behaviors. The researchers used this information to compare the Intervention and Education groups.

What did they find?

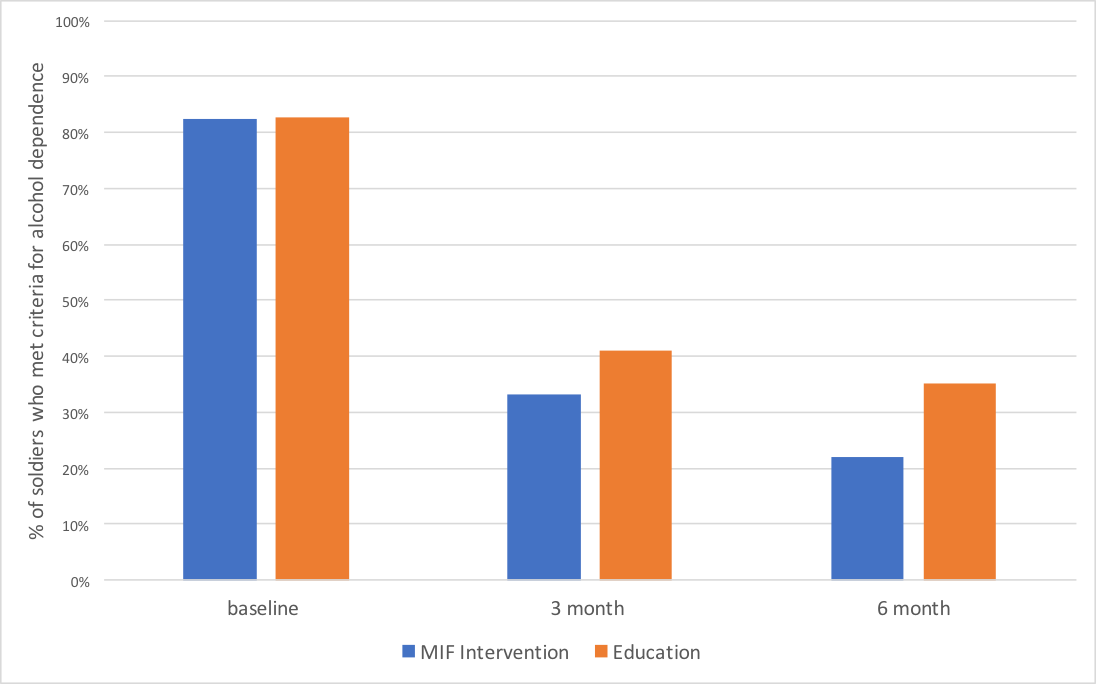

Both groups had a lower likelihood of being alcohol dependent over time; however, in the Intervention group, significantly fewer participants met criteria for alcohol dependence at follow-up when compared to the Education group (see Figure). Both groups also reported reduced substance use consequences over time. There were no significant effects on alcohol abuse or treatment-seeking behaviors over time.

Figure. Differences between the MIF intervention group and the Education group based on the percent of soldiers who met criteria for alcohol dependence at the baseline, 3 months and 6 months follow-ups. Figure adapted from Walker et al. (2017). Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

Brief interventions, such as MIF, allow clinicians to provide treatment and increase the opportunity for positive outcomes in a variety of settings. These findings partially support the efficacy of using MIF as a brief treatment for alcohol use disorder among active duty soldiers. Studies like these are important because they test brief interventions that might be more acceptable to service men and women and help to de-stigmatize treatment seeking.

Every study has limitations. What were the limitations in this study?

The authors excluded individuals with comorbid mental health problems. Many people have complex cases that involve both substance use and mental health problems, so adding a comorbid group would provide further insight on how using MIF would look in a more practical landscape.

For more information:

Learn more about alcohol use disorder and its symptoms here. If you or a loved one has problems with alcohol or other substance use, please visit our first steps to change here.

— Alec Conte

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

________________

[1] Participants were only included in the study if they met criteria for alcohol or other drug abuse or dependence according to the 4th edition of the diagnostic and statistical manual or mental health disorders (DSM-IV), were not currently being treated for substance use/mental health disorders, and were active-duty Army personnel. Participants were excluded if they screened positive for any other mental health conditions and/or were planning on deploying within a time period that would interfere with the study.