The DRAM, Vol. 10(2) – When it comes to problem drinking, there are limits on the “marriage advantage”

In 1958, British epidemiologist William Farr concluded, on the basis of groundbreaking research with married and non-married people, that “Marriage is a healthy estate…. The single individual is more likely to be wrecked on his voyage than the lives joined together in matrimony.” More recent research confirms the idea that marriage confers an advantage for one’s health (Schoenborn, 2004). However, when one spouse drinks heavily, it creates strain for the entire family and puts the other spouse at risk for problem drinking. In these cases, divorce might actually have some positive health consequences. Today, as part of our Special Series on Addiction within Relationships, The DRAM reviews a study testing the hypothesis that women ending their relationship with a problem drinker show improvements in their own drinking habits (Smith, Homish, Leonard, & Cornelius, 2012).

Methods

- The study used data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), a 2-wave nationally representative survey of the US adult population. For the current study, participants were 18,000+ female respondents who (1) reported being married or living as if married at Wave 1 (2001-2002) and (2) provided data at Wave 2 (2004-2005).

- The authors used past-year measures of potentially problematic drinking behaviors, including the following:

- How frequently participants consumed alcohol

- How many drinks participants usually consumed on drinking days

- How many alcohol abuse and dependence (AUD) symptoms participants endorsed within a NESARC-administered scale (e.g., Have you had a period when you ended up drinking more than you meant to?)1

- At both waves, participants also answered a single question regarding whether they were married to, or living as if married to, a partner with alcohol-related problems.2

- Finally, at Wave 2, participants indicated whether they experienced relationship dissolution between Waves 1 and 2. Relationship dissolution was defined as divorce, separation, or having stopped living with someone as if married.

- The authors tested whether, among those women who experienced relationship dissolution, the impact of relationship dissolution varied according to their partners’ problem drinking status at Wave 1.3

Results

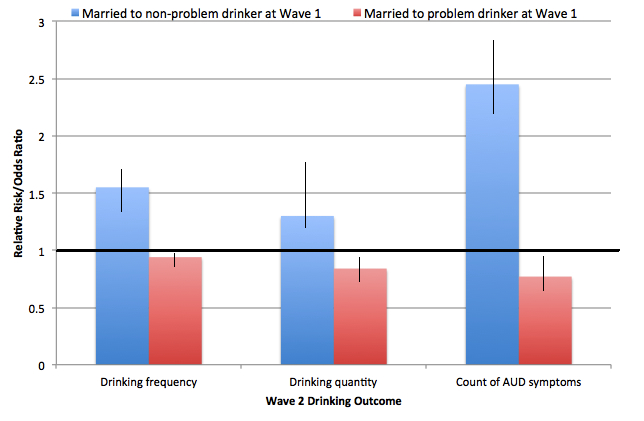

- Among women who were in a relationship with someone who was not a problem drinker at Wave 1, relationship dissolution increased the risk for all drinking-related outcomes at Wave 2 (see Figure).

- However, among women who were in a relationship with a problem drinker at Wave 1, relationship dissolution lowered the risk for drinking-related outcomes at Wave 2.

Figure. Wave 2 drinking outcomes according to whether participants were married to a problem drinker at Wave 1. Notes: Bars represent relative risk compared to women who remained in relationships. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Bars above the bold line indicate increased risk, and bars below the bold line indicate decreased risk. All effects are statistically significant. AUD = alcohol use disorder. Click image to enlarge.

Limitations

- The study included no direct data on partners’ drinking; the authors had to rely on proxy reports provided by wives, which might not have been accurate.

- Only women were included in the study; it is unclear whether husbands would demonstrate the same relationship between relationship dissolution and problem drinking.

- The data are helpful in establishing that divorce might be protective for problem drinking for wives, but they do not speak to why this effect occurred. In addition, because both changes in wives’ drinking habits and relationship dissolution occurred between Waves 1 and 2, it is possible that, in some cases, positive changes in wives’ drinking habits preceded relationship dissolution.

Conclusion

This research suggests that the effects of divorce on wives’ drinking habits depend on whether their partners showed problematic drinking habits before the divorce. Among wives whose partners had drinking problems, divorce was associated with positive changes in drinking habits. There are several potential reasons for this association: divorce might have removed the negative influence of the partner’s heavy drinking on the wife’s drinking habits. Or, divorce might have reduced feelings of stress or anxiety, so that wives were less likely to turn to alcohol to cope. Alternatively, as mentioned previously, wives who began to develop healthier drinking habits might have been more likely to divorce their heavy-drinking partners. Future research could explore these potential pathways, potentially by including more fine-grained measurements.

-Heather Gray

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

References

Farr, W. (1858). Influence of marriage on the mortality of the French People. In G. W. Hastings (Ed.), Transactions of the Natinal Association for the Promotion of Social Science (pp. 504-513). London: J. W. Park & Son.

Schoenborn, C. A. (2004). Marital status and health: United States, 1999-2002. Advance Data from Health and Vital Statistics (351), 1-32.

Smith, P. H., Homish, G. G., Leonard, K. E., & Cornelius, J. R. (2012). Women ending marriage to a problem drinking partner decrease their own risk for problem drinking. Addiction, 107(8), 1453-1461. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03840.x

1 In the NESARC, problem drinking symptoms were measured using the AUDADIS-IV (Grant, Dawson, & Hasin, 2001). The researchers also generated a yes/no measure of whether the participants endorsed enough symptoms to qualify for a diagnosis of past-year AUD, but we are not reporting that here.

2 Defined as “someone who has physical or emotional problems because of drinking; problems with a spouse, family or friends because of drinking; problems at work or school because of drinking; problems with the police because of drinking (e.g. drunk driving); or a person who seems to spend a great deal of time drinking or being hung over.”