The WAGER, Vol. 19(1) – From full house to no house: Housing stability and gambling-related problems

Housing stability refers to individuals’ likelihood of maintaining (or not) a permanent home. Although researchers have found that low-income individuals are likely to engage in gambling (Nower, Eyrich-Garg, Pollio, & North, 2014), surprisingly few studies of gambling and homelessness are available (e.g., Afifi et al., 2010; Declan et al., 2007). This week’s WAGER reviews a study that examined the relationship between housing stability and gambling-related problems (Gattis & Cunningham-Williams, 2011), as part of our Special Series on Homelessness and Economic Hardship.

Methods

- The authors recruited 315 individuals via advertising in newspapers and flyers.

- The 312 survey participants included individuals who reported gambling on at least one of 13 assessed gambling activities more than five times, and were at least 15 years old.

- During a telephone interview, participants completed the Computerized – Gambling Assessment Module (C-GAM; Cunningham-Williams, Cottler, Compton, & Books, 2003) and indicated whether they owned or rented their residence versus whether they lived with friends or another family member. Participants who owned or rented their residence were considered stably housed.

- C-GAM measures lifetime gambling risk based on the DSM-IV criteria for Pathological Gambling: 0 criteria = No Problems; 1-4 criteria = Subclinical gambling problems; 5 or more criteria = Clinical gambling problems.

- C-GAM includes demographic variables, as well as alcohol and drug modules, to measure lifetime alcohol and/or drug problems.

- The authors used chi-square analyses and a logistic regression analysis to determine whether lifetime gambling-related problems could predict housing stability, while controlling for demographic characteristics and lifetime substance use disorder.

Results

- 48 individuals (15%) reported unstable housing situations.

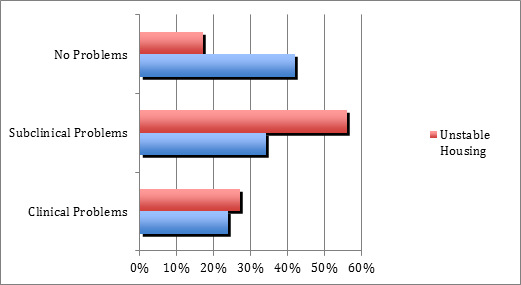

- As the Figure illustrates, individuals who reported clinical and subclinical gambling-related problems were more likely to report unstable housing situations.

- The logistic regression revealed that having subclinical gambling-related problems (Odds Ratio = .24), having lifetime substance use problems (Odds Ratio = .19), and never being married (Odds Ratio = .30) made housing stability less likely. Being Caucasian (Odds Ratio = 1.03) and being employed full-time (Odds Ratio = 9.24) or retired (Odds Ratio = 14.20) increased the likelihood of stable housing.

- Variables that did not predict housing stability included clinical gambling-related problems; lifetime alcohol problems; co-occurring alcohol and drug problems; current school status; college completion; gender; annual household income; and part-time employment.

Figure. Percentages of those with and without stable housing situations by gambling health status.

Limitations

- The sample was community-recruited, but not by random selection; therefore, people who were especially interested in the study topics might have been more likely to volunteer, and the generalizability of the findings is unclear.

- The housing stability variable was created for the purposes of this study, and therefore its psychometric properties (i.e., reliability and validity) are uncertain.

- Participants were 15 years and older, and it is unclear whether younger individuals understood and responded to the housing stability question in the same way as older respondents.

Conclusions

Although there are few studies of gambling and housing stability or homelessness, the complicating financial ramifications of gambling disorder suggest that this is an important topic of scientific inquiry. The current study suggests that the relationship between housing stability and gambling health is complicated, with subclinical gambling problems sharing an association with housing stability, but clinical problems failing to do so, after controlling for other factors. Stronger associations between clinical problems and other factors included in the analyses could explain this difference (e.g., sociodemographics or substance use history). Despite these mixed findings, this issue remains important and future work should pursue this question.

-Debi LaPlante

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

References

Afifi, T. O., Cox, B. J. , Martens, P. J., Sareen, J., & Enns, M. W. (2010) Demographic and social variables associated with problem gambling among men and women in Canada. Psychiatry Research, 178(2), 395-400.

Barry, D. T. Maciejewski, P. K. Desai, R. A. Potenza, M. N. (2007). Income differences and recreational gambling. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 1(3), 145-153.

Cunningham-Williams, R. M., Cottler, L. B., Compton, W. M., & Books, S. J. (2003). Computerized gambling assessment module (C-GAM). St. Louis, MO: Washington University.

Gattis, M.N. & Cunningham-Williams, R. M. (2011). Housing Stability and Problem Gambling: Is There a Relationship? Journal of Social Service Research, 1-10, DOI:10.1080/01488376.2011.598716

Nower, L., Eyrich-Garg, K. M., Pollio, D. E., & North, C.S. (2014). Problem Gambling and Homelessness: Results from an Epidemiologic Study. Journal of Gambling Studies DOI 10.1007/s10899-013-9435-0