The WAGER, Vol. 18(11) – Doomed to fail?: Predictors of problem gambling relapse

A large variety of factors determine whether someone will relapse into problem gambling after recovery. These range from genetics to environmental factors, and even include a person’s mood or stress level on a particular day (e.g.,Daughters et al. 2005). The few studies that examine these potential risk factors rarely look at more than one or two variables (e.g. Ledgerwood and Petry 2006) . This week’s WAGER reviews a prospective, longitudinal investigation into predictors of problem gambling relapse (Smith, Battersby, Pols, Harvey, Oakes, & Baigent, 2013). Studies such as these are valuable, because they allow us to track potential relapse factors and how they emerge within individuals.

Methods

- Researchers recruited 353 participants from four problem gambling treatment and support services in Adelaide, Australia.

- After implementing exclusion criteria (e.g. mental state, refusal etc) and taking follow-up assessment into account the final analytic sample consisted of 124 participants.

- Researchers administered a baseline assessment upon recruitment and follow-up assessments at 1-, 3-, 6-, and 12-months after baseline[1].

- During each assessment, participants completed scales[2] measuring six possible relapse predictors: gambling-related cognitions (i.e., various false beliefs about gambling behaviors, such as the illusion of control, that fuel pathological gambling behaviors), gambling-related urges, emotional disturbance, social support, sensation-seeking traits, and levels of work and social functioning.

- Researchers also administered the Victoria Gambling Screen (VGS) and assessed other gambling behaviors to assign, at each time point, one of three gambling outcome statuses: continuing to gamble, in remission (no gambling), or relapsed (gambling activity after a period in remission).

Results

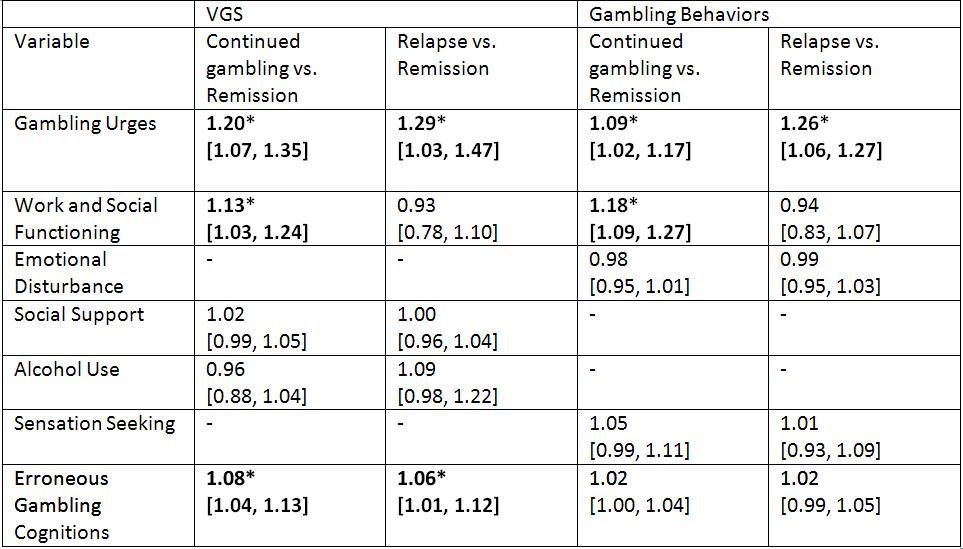

- Researchers compared rates of continued gambling/relapse vs. remission using scores on the VGS and gambling behaviors as outcome variables (see Table 1).

- Compared to others, people who reported more gambling urges, worse work and social functioning, and poorer gambling cognition (e.g., illusion of control), were more likely to relapse.

- Emotional disturbance, alcohol consumption, social support, and sensation seeking were not associated with relapse outcomes.

Figure. Odds ratios (OR) showing relationship of continued gambling/relapse vs. remission in gamblers based on several risk factor variables [95% Confidence Interval (CI)] Ratios marked with an asterisk “*” have a p value <.05. Click image to enlarge.

Limitations

- Over two-thirds of the analytic sample came from a single treatment site. Program-specific factors might have influenced the results.

- The sample size for this study is somewhat small, which limits power to detect significant effects.

Conclusions

The results of this study suggest that, in addition to more erroneous gambling cognition, increased gambling urges and more trouble with work and social adjustment significantly predict continued problem gambling behavior and relapse. The results of this research fall in line with previous studies that identified gambling urges and cognitions as predictors of relapse (Raylu & Oei, 2002). This study, however, incorporates far more risk factors that can affect relapse and continued gambling even in treatment and support-seeking gamblers. Relapse prevention techniques targeting these factors could work to head off these problems and reduce the likelihood of relapse. The next step would be to conduct research to design advanced interventions that target such factors so that relapse prevention efforts might contribute to individualized and successful long-term treatment for pathological gamblers.

– Emily Shoov & Daniel Tao

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

References

Daughters, S.B., Lejuz, C., Stron, D. R., Brown, R. A., Breen, R. B., & Lesieur, H.R. (2005). The relationship among negative affect, distress tolerance, and length of gambling abstinence attempt. Journal of Gambling Studies, 21(4), 363-378.

Ledgerwood, D. M., & Petry, N. M. (2006). What do we know about relapse in pathological gambling? Clinical Psychology Review, 26(2), 216-228.

Raylu, N., & Oei, T.P. (2002) Pathological Gambling: A comprehensive review. Clinical Psychology Review, 22(7), 1009-1061.

Smith, D.P., Battersby, M.W., Pols, R.G., Harvey, P.W., Oakes, J.E., & Baigent, M.F. (2013). Predictors of relapse in problem gambling: A prospective cohort study. Journal of Gambling Studies. Online first.

________________

[1] Due to time constraints, participants enrolled after September 2008 did not participate in the 12-month follow up.

[2] Scales used were Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS), Trait Anxiety Inventory (TAI), Gambling Urge Scale (GUS), Gambling Related Cognition Scale (GRCS), Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), Arnett Inventory of Sensation Seeking (AISS), Multidimenstional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS), and the Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS)