ASHES, Vol. 8(9) – Should you smoke that cigarette? The efficacy of question-based warning labels

In a previous issue of ASHES, we reported that graphical cigarette warning labels had little effect on smoking behavior. Recently, the D.C. District court of appeals upheld an earlier decision striking down these graphic warning labels (R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. v. FDA, No. 11-5332 (D.C. Cir. Aug. 24, 2012)). One major factor for the decision was the FDA’s inability to prove the efficacy of the graphical warning labels. In light of this decision, this week ASHES reviews a study investigating whether altering the style of warning messages improves their ability to alter smoking beliefs (Glock, Müller, & Ritter, 2012). Glock et. al. postulate that defensive responses of smokers against confrontational text and graphical warning labels might mean that they will be less likely to change their smoking behaviors following exposure to such labels. They propose that by rewriting warning labels as questions, or omitting them altogether, smokers will create their own warning messages internally and feel less threatened by the message.

Methods

Researchers recruited 60 students from Saarland University who were daily smokers.

- The researchers divided the cohort into 4 equal groups and presented each group with one of four types of images on different sets of 15 cigarette packages.

- Each cigarette package set included one specific type of warning label: standard textual warning labels; graphic warning labels; textual warning labels reworked into questions; or no warning labels at all.

- Participants completed a questionnaire assessing their smoking habits prior to and after viewing the cigarette packages.

- Participants rated their perceived risk for six smoking-related diseases on a scale from 0 (no risk) to 9 (highest risk).

- The researchers conducted an a priori contrast comparing the question and control groups with the graphic and textual groups.

Results

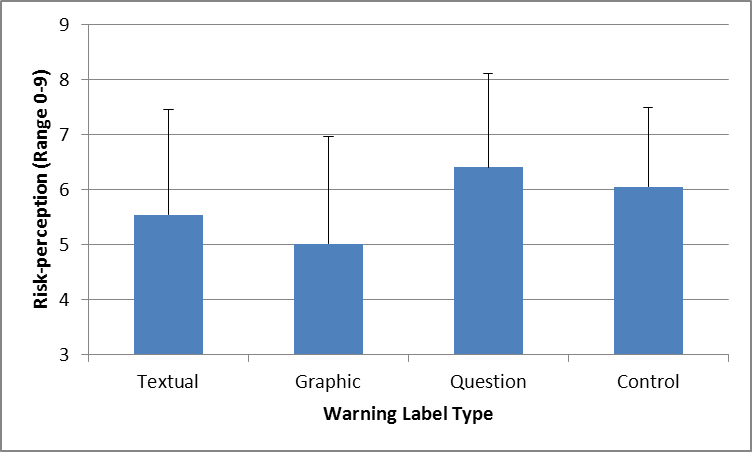

- The researchers found that there was a significant difference between the Question/Control and Textual/Graphical warning label group, such that the Question/Control group reported higher perceived risk. (Figure 1) (F(1,55) = 4.32, p=0.04, np2=0.07)

- There was no significant difference between the textual and graphical warning label (t(28) = 0.61, d = 0.22, p = .54) or between the question warning label and control group (t(27) = 0.73, d = 0.27, p= .47).

Figure. Mean score and standard deviation of smoking related risk perception (adapted from Glock et al. 2012). Click image to enlarge.

Limitations

- The small sample size limits the power of the study. (n=15 for each group)

- The cohort consists solely of college students, which limits the generalizability of the results.

- Young smokers have not smoked as many years as older adults and might not be as worried about health consequences as they seem less relevant in the short term.

- This population intrinsically has a higher level of education than young adults who have not attended college and might already be more informed about the risks of smoking.

- The novelty of a new warning label effect might be the cause of the difference in risk perception as current smokers might be accustomed to the present warning labels.

- However, the authors note that the graphic warning label had yet to be introduced in Germany where the experiment took place.

- Smoker risk-perception does not necessarily result in a change in smoking behavior.

Discussion

Graphic warning labels have been scrutinized since their introduction and it is unclear how effective they are as tools for smoking cessation (Borland, Wilson, Fong et al., 2009; McCool, Webb, Cameron et al., 2012). Glock et al. show that smokers presented with graphical and textual warning labels have a lower smoking risk-perception compared with smokers in both the control group and question label group. Furthermore, they argue that

although question type labels result in the same level of risk-perception as the control condition (and higher than textual/graphical), a warning label of some sort is still necessary to inform smokers. Additional research is required

to determine the effectiveness of question based warning labels and from there we will be able to determine if they prove to be a viable alternative.

-Jed Jeng

References

Borland, R., Wilson, N., Fong, G. T., Hammond, D., Cummings, K. M., Yong, H.-H., et al. (2009). Impact of graphic and text warnings on cigarette packs: findings from four countries over five years. Tobacco Control, 18, 358-364.

Glock, S., Müller, B. C., & Ritter, S. M. (2012). Warning labels formulated as questions positively influence

smoking-related risk perception. Journal of Health Psychology, Online publication.

McCool, J., Webb, L., Cameron, L. D., & JHoek, J. (2012). Graphic warning labels on plain cigarette packs: Will

they make a difference to adolescents? Social Science & Medicine, 74(8), 1269-1273.

R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. v. U.S.F.D.A., No. 11-1482, 845 F.Supp.2d 266, 2012 WL 653828 (D.D.C. Feb. 29, 2012)

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.