Addiction & the Humanities, Vol. 8(6)—Help, I’m alive: The pathologizing of everyday life in direct pharmaceutical advertising

This week, we begin a series focusing on addiction and advertising. The next three issues of Addiction & the Humanities will explore the relationship between advertisements, drug use and public perceptions of addiction.

The use of psychotropic medications, including anti-depressants, stimulants, and anti-psychotics, is strong and growing among Americans. The total number of Americans taking antidepressants doubled between 1996 and 2005 (Olfson, 2009),and American children are approximately three times more likely to be prescribed psychotropic medication than children in some European countries (Zito, 2008).

Some researchers (e.g., Zito, 2008) suggest that pharmaceutical advertising plays a role in these trends by targeting people who would not meet formal criteria for a psychiatric condition. This week’s edition of Addiction & the Humanities examines American direct-to-consumer (DTC) and direct-to-physician (DTP) marketing of psychotropic medication over the last fifty years.

Simple Solutions to Everyday Problems

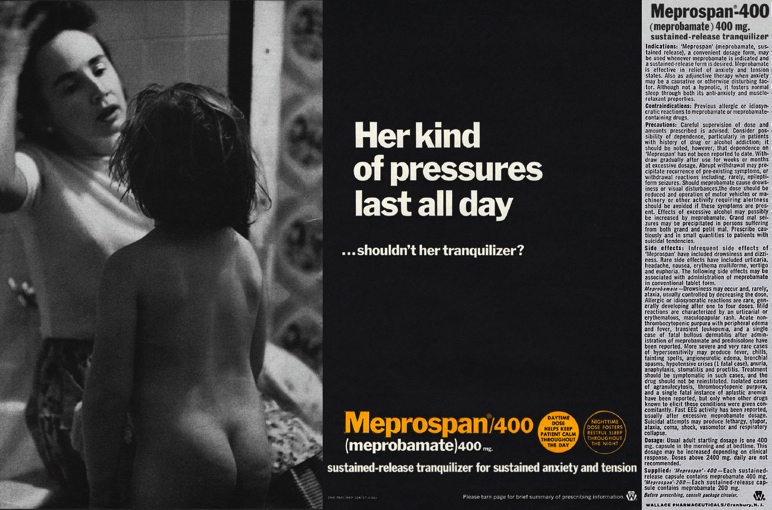

Pharmaceutical advertising proliferated in medical journals during the 1950s and 1960s (Hanganu-Bresch, 2008).This advertisement for Meprospan appeared in a medical journal in 1967, when housewives across the nation commonly were being prescribed Meprospan for “insomnia, anxiety, and emotional upsets.” Soon, the drug was marketed as a panacea for all domestic ills. The woman in this advertisement is depicted as harried and at the end of her rope—presumably a pathological state requiring medication. The camera angle gives us a full view of the woman’s face as her child apparently is demanding something from her. We are encouraged to make a connection between this stressful but commonplace situation and mental illness. A physician who flipped past this advertisement during his morning read could listen to his female patients’ complaints about the stress and drudgery of housework, and think back to an advertisement that presented these as problems worthy of solving with a tranquilizer. The ad invites doctors to identify with the woman's mood and stimulate empathy with its message—"Her kind of pressures last all day.” This ad encourages physicians to prescribe Meprospan—instead of other alternative ways of dealing with this sort of problem—and by extension, for patients who look like this.

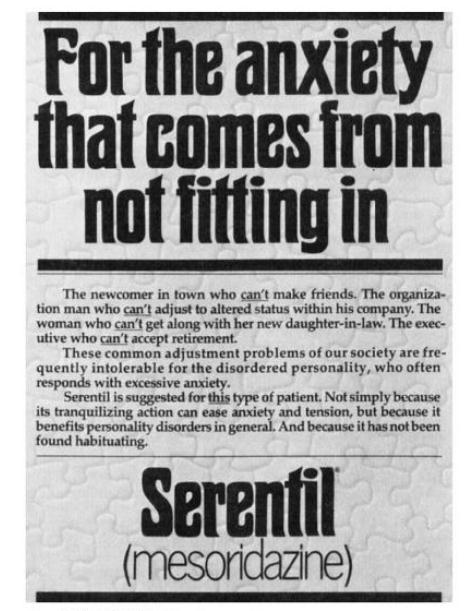

During the 1960s, the pharmaceutical company Sandoz placed ads for its new tranquilizer, Serentil, in medical journals. Sandoz marketed Serentil as a drug that could deal with stress that a shy businessman might feel. This text advertisement from the late 1960s presents Serentil as a solution “for the anxiety that comes from not fitting in,” for the type of patient who “responds with excessive anxiety” and “can’t make friends.” Again, these stressful but commonplace situations are marketed as conditions so pathological they necessitate medication.

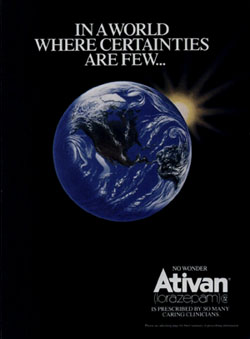

This advertisement from the 1980s for Ativan, a medication commonly prescribed for anxiety, shows a planet surrounded by darkness. “In a world where certainties are few, no wonder Ativan is prescribed by so many caring clinicians.” The ambiguities of everyday life are cause for concern, and now, reason for medication. This advertisement for Ativan seems to reflect many of the uncertainties that Americans might have felt during the early 1980s as a result of globalization, financial recession, and the nuclear arms race with the Soviet Union. The jump from “uncertainty” to “clinical anxiety” lies in the implicit message of this advertisement.

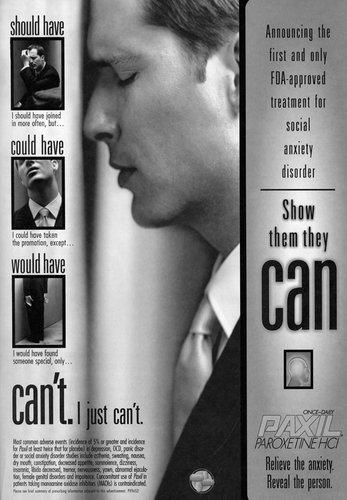

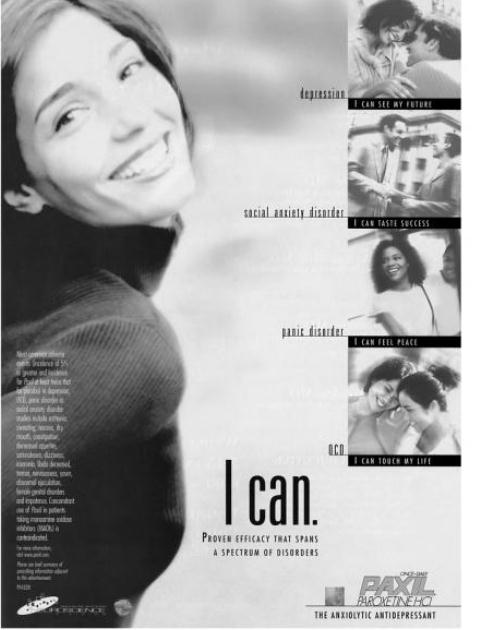

In the 1990s, GlaxoSmithKline marketed the antidepressant Paxil for treatment of social phobia, or social anxiety disorder. Here, two advertisements ignore the diagnostic criteria associated with social anxiety disorder (i.e., extreme fear, physiological reactions, and an extreme avoidance of certain situations ((APA), 1994) to present Paxil as a solution for the problem of not successfully connecting with people.

(Paxil, 1999, American Journal of Psychiatry)

These two advertisements for Paxil lead us to believe there is a connection between relatively common situations and the clinical condition of social anxiety disorder. In the first, Paxil is the solution for turning social dysfunction (“I should have joined in more often,” “I would have found someone special”) into function (“Show them they can.”) In the second, Paxil is a “one-stop shop” for not just social anxiety disorder but also depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and panic disorder.

The key words in all of these advertisements— “pressures,” “certainties,” “can’t”— sidestep clinical language in favor of vague definitions of emotional disorder. Again, the message is: You don’t need to live with everyday stress. There’s an easy way out.

Consumers respond positively to these messages. One-fifth of Americans have asked their doctor for a drug after seeing it advertised (Hanganu-Bresch, 2008). And physicians largely comply, even when the patient has no psychiatric diagnosis. For instance, a study of antidepressant use in private health insurance plans found that 43% of those who had been prescribed antidepressants had no psychiatric diagnosis in their records (Larson, 2007).And for many Americans, medication is their only form of mental health care. As rates of antidepressant use increased, rates of psychotherapy decreased (Olfson, 2009).

No Easy Way Out

Is there something harmful about the suggestion, implicit or explicit in these ads, that medication is the solution to relatively common and mild forms of distress, problems that may not even require clinical intervention? On one hand, these advertising campaigns have helped remove some of the stigma of mental illness and have prompted greater use of mental health services. For people who are predisposed to experience greater levels of distress, and for people coping with painful forms of mental illness, these medications can make the difference between life and death, survival and suffering.

For more mild and temporary forms of distress, however, it could be that medication interferes with normal coping mechanisms. Some suffering or pain might be instructive, and possibly even necessary for learning and personal growth to occur (Scherer, 1984). Humans learn and experience life through contrasts. The contrast between distress and pleasure is no exception. A reduced capacity to cope with distress is presumed to be integral to substance use disorders, according to the self-medication hypothesis (Khantzian, 1997). The self-medication hypothesis suggests that patients self-medicate painful feeling states. These advertisements might be harmful to the extent that they encourage medication as an easy alternative to learning more active coping strategies, seeking spiritual or mental health counseling, and making long-lasting behavioral changes.

Conclusion

In the next edition of Addiction and the Humanities, we will investigate expressions of addiction in popular advertising.

For now, though, direct advertising of psychotropics leads us to ask some potentially unsettling questions about what constitutes mental illness, what can be treated, and whether we should view everyday worries as abnormal. These are tough questions. Perhaps an additional benefit of direct advertising is that it forces us to continue to have these discussions.

-Kat Belkin

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

References

(APA), A. P. A. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, Fourth Edition. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association.

Arnold, M. (2006). 40 years of DTC. Medical Marketing & Media. Retrieved from http://www.mmm-online.com/about/section/68/

Hanganu-Bresch, C. (2008). Faces of Depression: A Study of Antidepressant Advertisements in the American and British Journals of Psychiatry, 1960-2004. Unpublished Graduate Dissertation, University of Minnesota.

Khantzian, E. J. (1997). The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: A reconsideration and recent applications. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 4(5), 231-244.

Larson, M., Miller, K., & Fleming, K. J. (2007). Treatment with Antidepressant Medications in Private Health Plans. Administration And Policy In Mental Health And Mental Health Services Research, 34(2), 116-126.

Olfson, M., Marcus, S.C. (2009). National Patterns in Antidepressant Medication Treatment. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66(8), 848-856.

Scherer, J. (1984). "How people learn: Assumptions for design." Training & Development Journal, 38(1), 64-65.

Tang, M., &Hou, G. (2011). Chronic stress impairs learning and memory and down-regulates expression of FGF2 in hippocampus and prefrontal cortex of rats. ActaPsychologicaSinica, 43(7), 784-791.

Zito, J. M., Safer, D. J., van den Berg, L., Janhsen, K., Fegert, J.M., Gardner, J.F., Glaeske, G., Valluri, S. (2008). A three-country comparison of psychotropic medication prevalence in youth. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 2(26), 8.