The DRAM, Vol. 7(9) – Slipping through the cracks: Underdiagnosis of comorbid mental illness among repeat DUI offenders

This week, the DRAM continues its series focusing on driving under the influence (DUI). This is the last of five issues concentrating on the body of recent DUI research. In the first four issues, DRAM Vol. 7(5), DRAM Vol. 7(6), DRAM Vol. 7(7) , and DRAM Vol. 7(8), we addressed DUI-related trends, methods to detect heavy alcohol consumption and recidivism, the use of ignition interlock devices to reduce DUI behavior, and different psychiatric profiles among DUI offenders.

Repeat DUI offenders represent a population of individuals who are at high risk for co-occurring psychiatric disorders (Lapham, C’De Baca, McMillan, & Lapidus, 2006). However, in a variety of clinical settings, such as addiction treatment facilities and DUI offender programs, offenders often do not undergo comprehensive screening for psychiatric disorders (Nelson et al., 2007; Shaffer et al., 2007). This week, the DRAM reviews a study that evaluated the extent to which repeat DUI offenders are diagnosed with comorbid psychiatric disorders during mandatory treatment (McMillan et al., 2008).

Method

- The sample consisted of 233 repeat DUI offenders (86% male, Mage= 38.5, 72% White) scheduled to undergo mandatory alcohol treatment at seven licensed facilities.

- The investigators assessed their sample with a battery of surveys, using the following measures:

- The Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI; Robins, Helzer, Ratcliff, & Seyfried, 1982)—assesses whether respondents meet diagnostic criteria for a range of mental health disorders. The investigators used the CIDI to assess disorders occurring within the past 12 months.

- The Treatment Abstraction Form (Timken, 2001)—gathers data from treatment charts of persons convicted of DUI and sentenced to mandatory treatment, including mentions of alcohol or drug use disorders in an offenders’ medical records as well as any psychiatric comorbidity identified during the treatment process.

Results

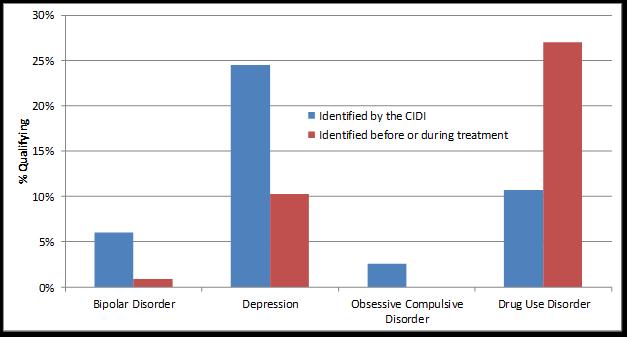

- 92.9% of participants with bipolar disorder, 68.4% of those with depression, and 100.0% of those with OCD went undiagnosed for these disorders during treatment.

- The CIDI identified just over 10% of the sample as qualifying for a drug use disorder. Participants were overdiagnosed as having drug use disorders during treatment. Treatment records identified more than 25% as having drug use disorders; approximately 24.6% (adjusted) of defendants who were not identified as having a drug use disorder on the CIDI were diagnosed with such during treatment.

- The CIDI is a valid and reliable instrument for assessing mental health disorders in general populations; however, its validity has not been assessed in repeat DUI populations. There is no gold standard for diagnosis, and the CIDI “diagnosis” is a proxy just as are real-time clinician impressions for a patient’s “actual” mental health status. Absent a gold standard, we cannot determine whether the clinician or the CIDI are correct.

- The CIDI was administered prior to treatment admission, and the records analyzed to determine disorders recognized during treatment included observations made later (i.e., during treatment), as well as records that potentially pre-dated CIDI administration. Therefore, mental health status might have been different at the time of each assessment.

- It is possible that the treatment programs’ patient records were not consistently maintained or accurately reflected clinicians’ diagnoses. Clinicians might have diagnosed patients consistently with the CIDI, but the diagnosis not properly recorded. Programs might not have had an alternative diagnosis record keeping system, but nevertheless made some diagnoses that were in line with the CIDI.

Figure. A comparison of comorbid psychiatric disorders identified by the CIDI and treatment records among repeat DUI offenders. Cases identified through treatment as qualifying for a given disorder are not necessarily the same cases as those identified by the CIDI. Click image to enlarge.

Limitations

- The CIDI is a valid and reliable instrument for assessing mental health disorders in general populations; however, its validity has not been assessed in repeat DUI populations. There is no gold standard for diagnosis, and the CIDI diagnosis is just as much of a proxy as real-time clinician impressions for a patient’s “actual” mental health status.

- The CIDI was administered prior to treatment admission, and the records analyzed to determine disorders recognized during treatment included observations made later (i.e., during treatment), as well as records that potentially pre-dated CIDI administration. Therefore, mental health status might have been different at the time of each assessment.

- It is possible that the treatment programs’ patient records were not consistently maintained or accurately in line with clinicians’ diagnoses. Patients may have been diagnosed correctly by program therapists, but the diagnosis not properly recorded. Programs may not have had an alternative diagnosis record keeping system, but may have nevertheless made diagnoses that aligned with the CIDI.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that mental health disorders other than drug use disorders likely are underdiagnosed within DUI-related treatment. Underdiagnosis of comorbid psychiatric conditions during mandatory treatment likely stands in the way of improving outcomes for this patient population. Ignorance of complicating diagnoses might result in increased rates of relapse and recidivism in an already vulnerable population. Future research efforts should focus on improving pathways to identifying and treating DUI offenders with comorbid conditions.

The Division on Addictions is in the process of developing and testing CARS, a computerized assessment and referral system that guides DUI program staff through a standardized mental health assessment with their clients. For more information about our efforts in this area, please visit www.divisiononaddictions.org.

-Katerina Belkin

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

References

Lapham, S. C., Kapitula, L. R., C’de Baca, J., & McMillan, G. P. (2006). Impaired-driving recidivism among repeat offenders following an intensive court-based intervention. Acc Analys Prevent, 38, 162–169.

Lapham, S. C., C’De Baca, J., McMillan, G. P., & Lapidus, J. (2006). Psychiatric disorders in a sample of repeat impaired-driving offenders. J Stud Alcohol, 67(5), 707-713.

McMillan, G. P., Timken, D. S., Lapidus, J., C’De Baca, J., Lapham, S. C., & McNeal, M. (2008). Underdiagnosis of comorbid mental illness in repeat DUI offenders mandated to treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat, 34(3), 320-325.

Nelson, S. E., LaPlante, D. A., Peller, A. J., LaBrie, R. A., Caro, G., & Shaffer, H. J. (2007). Implementation of a computerized psychiatric assessment tool at a DUI treatment facility: a case example. Adm Policy Ment Health, 34(5), 489-493.

Robins, L. N., Helzer, J. E., Ratcliff, K. S., & Seyfried, W. (1982). Validity of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule, Version II: DSM-III diagnoses. Psychological Medicine, 12, 855– 870.

Shaffer, H. J., Nelson, S. E., LaPlante, D. A., LaBrie, R. A., Albanese, M., & Caro, G. (2007). The epidemiology of psychiatric disorders among repeat DUI offenders accepting a treatment-sentencing option. J Consult Clin Psychol, 75(5), 795-804.

Timken, D. S. (2001). TAB (Treatment Abstraction Form). Albuquerque, NM7 Behavioral Health Research Center of the Southwest.