Addiction & the Humanities, Vol. 7(8): Are We “Hooked”? The Success of Addiction Memoirs

With the number of available addiction memoirs, one would expect that the last thing the public wants is yet another story about addiction and recovery. However, the genre of addiction memoirs has thrived for a very long time. Writers and non-writers alike have documented their battles with drug addiction in books that have become popular with readers who are in recovery, as well as readers who simply are curious about the issue. Despite their popularity, many observers continue to criticize addiction memoirs as being everything from unnecessary to dangerous. Readers’ reviews on websites like Amazon.com and GoodReads.com include these reproaches. A common gripe is that addiction memoirs all have the same plot: bad childhood leading to drug abuse, ruining one’s life, recovering, and then writing about it. For those who seek novelty in their reading experiences, addiction memoirs that follow this trajectory simply add to the ether.

Why do Readers Crave Addiction Memoirs?

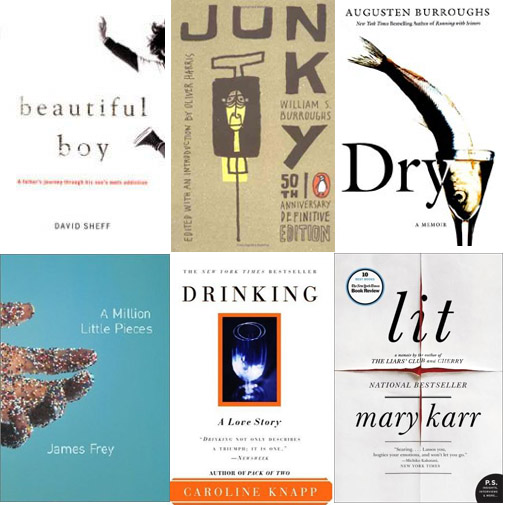

There is a multitude of reasons that readers might seek addiction memoirs. One reason for their ongoing popularity might lie in people’s truth-seeking nature. As human beings, we often make sense of ourselves and our lives through narrative. Novels can point us to universal truths, but memoirs have the power to represent what happened. Literature can create benchmarks for life. Angry reactions to expositions of fake memoirs reveal the value that society places on truth. When James Frey’s A Million Little Pieces, a memoir about the author’s alcohol and cocaine addiction, was revealed to be fictitious, the news created a public outcry (Frey, 2005).Reader reviews on Amazon reveal frustration with Frey’s perceived harmful dishonesty—“I am an alcoholic and James Frey made me feel violated.” “Frey’s tall tale is dangerous for anyone seeking help.” We covered the Frey scandal in a former BASIS (Hazra, 2006).

Another potential reason for the ongoing popularity of addiction memoirs is that humans are curious. Many people get a kick out of reading about others' interesting habits and compulsions. A public hanging has never failed to draw an audience, and seeing others mess up often inspires a feeling of confidence in readers’ choices; memoir readers often get the feeling that “it’s not so bad.” Fascination’s bitter alter ego, schadenfreude, can accompany this experience.

Yet another reason for the popularity of the addiction memoir is that people use them for self-help. It is possible and likely that people who are dealing with their own addiction find that reading about another person’s struggles resonates with them in a positive way. Such sharing is a central tenant of many self-help groups, like Alcoholics Anonymous. For those who are motivated to find treatment and embark on the long road to recovery, a personal memoir can provide valuable information, support, and motivation.

Why do Authors Create Addiction Memoirs?

Just as people have different motivations for picking up an addiction memoir, writers have different motivations for writing and selling them. Beyond the obvious financial reasons, some authors find confession to be cathartic. Writing about the darker parts of one’s past can be helpful for someone who wants to get demons out into the open. Alternatively, some authors might write their addiction memoirs to help others, and not just themselves.

Historically, confessional memoirs have been irresistible to the public for a very long time. As Daniel Mendelsohn of The New Yorker puts it, the “arc from utter abjection to improbable redemption, at once deeply personal and appealingly universal,” is one that has been replicated throughout literary history. According to Mendelsohn, the redemptive memoir has its roots in the Confessions of St. Augustine, whose tale of his spiritual journey was a call to others to be faithful. Mendelsohn’s analysis finds a dramatic shift in the nature of memoirs that occurred in the shift from the Age of Faith to the Age of Reason (Mendelsohn, 2010). He credits Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s “Confessions” as the instrumental force behind the secular transformation of “confession” into a secular, public, and purely literary gesture.

Today’s tell-all addiction memoir seems to be a curious hybrid of the purely spiritual and the purely confessional aspects of the memoir genre. The lurid details of drug withdrawal, the car-wreck allure of the relapse, and the poor choices made while under the influence, all draw fascination from the average reader and fall on the side of the confessional. Augusten Burroughs’ Dry is a good example that comes to mind. Dry chronicles the author’s attempt to stay sober after treatment for alcohol dependence (Burroughs, 2004). When Burroughs relapses, readers get every detail of the fallout. He does not spare the grisly details of his lows—the weakness, the prostitutes, crack houses, and self-injurious behavior. He provides so many details that the memoir often seems to veer into sensationalism.

The appeal to a higher power that is present in many addiction memoirs—for example, most contain references to Alcoholics Anonymous or a 12-step program—constitutes the spiritual aspect. Those who recover and write about it often conclude that finding a higher power was the key to their continuing sobriety. And, fighting one’s way to sobriety, soaring to healthy heights despite seemingly impossible lows contains more than a trace of the ancient redemption tale.

Concluding Thoughts

By now, it should be apparent that there are many reasons why people write and read addiction memoirs. We might find ourselves lauding one writer’s motivation to inform and instruct over another writer’s motivation to profit and make money by selling a memoir. Questions about usefulness and value come to mind in the face of the sheer volume of addiction memoirs in the marketplace. The better question might be whether it is useful to make normative claims about who should write memoirs about addiction, and whether they are worth reading.

It is important to remember that, unfortunately, many stories of addiction do not end in recovery. Of the people who do struggle with substance dependence, few go on to write about it. Memoirs are a by-product of selection bias, and not an indicator of the similarity of all addiction stories, despite the many redemptive endings. The author’s personal struggles with addiction often continue beyond the pages, and not all recoveries fit neatly into a final chapter and epilogue. Moreover, these redemptive endings need not be any less rewarding for their inevitability. Every personal story contains a unique voice and a chance for someone to turn their life around after reading it—whether or not that was the author’s intended purpose. For those who seek some form of truth about addiction and recovery, a personal account could be one of the most accessible ways to find it. In the preface that Frey added to A Million Pieces, he writes about the revelation that his memoir was part fantasy, “I hope these revelations will not alter [readers’] faith in the book’s central message—that drug addiction and alcoholism can be overcome, and there is always a path to redemption if you fight to find one.”

References

Burroughs, A. (2004). Dry. New York, Picador.

Frey, J. (2005). A Million Little Pieces. New York, Anchor.

Hazra, S. “Frey's Million Little Lies with Oprah.” (February 2010). From Addiction & The Humanities in BASIS, a website of the Division on Addictions at Cambridge Health Alliance, an affiliate of Harvard Medical School (www.divisiononaddictions.org).

Mendelsohn, D. "But Enough About Me." (January 2010). From The New Yorker Online. http://www.newyorker.com/arts/critics/books/2010/01/25/100125crbo_books_mendelsohn