The Wager Vol. 14(6) – BBGS vs. NODS-CLiP: Which Brief Screen for Pathological Gambling Wins the Battle of Psychometrics?

The process of screening for addictive behaviors is moving from research labs into the mainstream of public health practice (Anderson, Aromaa, Rosenbloom, & Enos, 2008). Most people and programs that consider administering public health screens face significant temporal and financial restrictions. Consequently, the development of brief screens that can identify the most people in need of treatment, without also generating many false positives, is critical. Among the general population, pathological gambling (PG) is a relatively rare disorder (Kessler et al., 2008; Petry, Stinson, & Grant, 2005). As a result, public health workers tend to screen for and detect PG less often than other more prevalent expressions of addiction, such as alcohol and other drug dependence. Until now, there were only two brief screens for detecting PG among the general population (i.e., the Lie/Bet Questionnaire, and the MAGS 7, respectively; Johnson et al., 1997; Shaffer, LaBrie, Scanlan, & Cummings, 1994). This week the WAGER compares two new, independent and nearly simultaneously published reports focusing on the development of brief screens for PG (Gebauer, LaBrie, & Shaffer, in press; Toce-Gerstein, Gerstein, & Volberg, in press).

Methods

- The Brief Bio-Social Gambling Screen (BBGS; Gebauer et al., in press)

- Gebauer et al. developed the BBGS using past year DSM-IV PG items from the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule IV (AUDADIS-IV; Grant, Dawson et al., 2003) that was included within the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC; Grant, Moore, & Kaplan, 2003).

- The NESARC survey collected information from a United States nationally representative random sample of individuals (N=43,093) from the general household population.

- Gebauer et al. targeted participants who endorsed five or more DSM-IV symptoms or signs as the group of pathological gamblers (PGs) to be distinguished from participants who failed to meet these criteria.

- The researchers used data analytic procedures, including step-wise entry, step-wise elimination, and combinations of minimal sets of DSM-IV criteria, to identify the subset of DSM-IV criteria that was sufficiently sensitive to identify PGs correctly, and specific enough to exclude non-PGs from being incorrectly classified as PGs (i.e., false positives).

- Gebauer et al. developed the BBGS using past year DSM-IV PG items from the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule IV (AUDADIS-IV; Grant, Dawson et al., 2003) that was included within the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC; Grant, Moore, & Kaplan, 2003).

- The NODS-CliP (Toce-Gerstein et al., in press)

- Toce-Gerstein et al. (in press) developed the NODS-CLiP using lifetime DSM-IV PG items from the NORC Diagnostic Screen for Gambling Disorders (NODS; Gerstein et al., 1999).

- Researchers administered the NODS to participants (N=17,180) in eight different general adult population field studies.

- Toce-Gerstein et al. targeted participants who endorsed five or more DSM-IV symptoms or signs as the group of PGs to be distinguished from participants who failed to meet these criteria.

- The researchers developed the NODS-CliP by analyzing how well each possible subset of 2-4 NODS items identified PG.

- Toce-Gerstein et al. (in press) developed the NODS-CLiP using lifetime DSM-IV PG items from the NORC Diagnostic Screen for Gambling Disorders (NODS; Gerstein et al., 1999).

Results

- Both the NODS-CLiP and the BBGS offer three items as a brief screen that can identify PGs from the general population.

- NODS-CLiP

- Loss of Control: Have you ever tried to stop, cut down, or control your gambling?

- Lying: Have you ever lied to family members, friends or others about how much you gamble or how much money you lost on gambling?

- Preoccupation: Have there been periods lasting 2 weeks or longer when you spent a lot of time thinking about your gambling experiences, or planning out future gambling ventures or bets?

- BBGS

- Withdrawal: During the past 12 months, have you become restless, irritable or anxious when trying to stop/cut down on gambling?

- Deceive: During the past 12 months, have you tried to keep your family or friends from knowing how much you gambled?

- Bailout/Need Money: During the past 12 months, did you have such financial trouble that you had to get help with living expenses from family, friends, or welfare?

- NODS-CLiP

- Psychometric Values

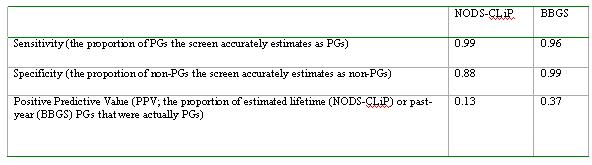

- Table 1 summarizes the psychometric values for both the NODS-CLiP and the BBGS (i.e., Sensitivity, Specificity and Positive Predictive Values).

Table 1. Comparing the Psychometric Values of the NODS-CLiP and the BBGS

*Click image to enlarge, or adjust your browser's zoom setting.

*Click image to enlarge, or adjust your browser's zoom setting.

Limitations

- The NODS-CliP identified lifetime PG; the BBGS identified past-year PG.

- Using a lifetime context for symptom clustering is problematic. This strategy yields more endorsed problems than past-year time frames for symptom identification; further, using a lifetime frame for screening is inconsistent with the process of making a clinical diagnosis. For example, research shows that gambling related problems evidence considerable waxing and waning from year to year (LaPlante, Nelson, LaBrie, & Shaffer, 2008). As a result, the NODS-CliP might not reflect current problems that often associate with treatment seeking. The BBGS features current problem identification. The different PPVs, in part, reflect this circumstance.

- Because the NODS-CLiP uses a lifetime context for symptom identification, the PGs who screened positive might not present as PGs currently. As a result, the NODS-CLiP’s sensitivity, its apparent strength (i.e., 0.99 for the NODS-CLiP vs. 0.96 for the BBGS), is uncertain for applications seeking to identify current PG.

- Both studies were limited because both teams of researchers selected PG items from those that currently were available in the DSM-IV.

- The DSM-IV criteria do not represent an exhaustive list of sequelae associated with PG and there is no empirical evidence that, despite its reliability, the DSM-IV includes conceptually valid diagnostic criteria. In fact, the efficacy of both screens serves to demonstrate that some of the DSM diagnostic criteria for PG fail to discriminate it adequately from those who do not suffer with this problem.

- Both studies are subject to the problems associated with data obtained exclusively from self-report.

Conclusions

Which screen wins? One clear advantage of the BBGS is the assessment of past year PG, which is consistent with clinical practice, compared to lifetime PG. Beyond this, determining the answer really depends on the goal of screening. For most clinical programs, time and money are precious resources that cannot be wasted. If an agency was to conduct follow-up evaluations with those identified as PGs by the NODS-CLiP, we would expect only one in eight to be identified correctly as a PG; however, of those identified as a PG by the BBGS, approximately one in three would be identified correctly as a PG. A screen that yields many false positives (e.g., 7 for every 8 screened), and does not maximize specificity, is best to garner liberal estimates of problems, but has limited clinical utility. Therefore, for clinical programs, a screen with superior specificity and high sensitivity makes the most sense (i.e., BBGS). Nevertheless, for researchers and others who simply want to identify the most PGs possible, without care for false positives, the slight sensitivity advantage evidenced by the NODS-CLiP might make it more attractive. Ultimately, you will have to decide the goal of screening, and then pick the measure that best achieves that goal.

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

References

Anderson, P., Aromaa, S., Rosenbloom, D., & Enos, G. (2008). Screening and Brief Intervention: Making a Public Health Difference. Boston: Join Together.

Gebauer, L., LaBrie, R. A., & Shaffer, H. J. (in press). Optimizing DSM-IV classification accuracy: A brief bio-social screen for gambling disorders among the general household population. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry.

Gerstein, D., Murphy, S., Toce, M., Hoffmann, J., Palmer, A., Johnson, R., et al. (1999). Gambling Impact and Behavior Study: Report to the National Gambling Impact Study Commission. Chicago: National Opinion Research Center.

Grant, B., Dawson, D., Stinson, F., Chou, P., Kay, W., & Pickering, R. (2003). The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): Reliability of alcohol consumption, tobacco use, family history of depression and psychiatric diagnostic modules in a general population sample. Drug & Alcohol Dependence, 71, 7-16.

Grant, B., Moore, T., & Kaplan, K. (2003). Source and Accuracy Statement: Wave 1 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Johnson, E. E., Hamer, R., Nora, R. M., Tan, B., Eisenstein, N., & Engelhart, C. (1997). The Lie/Bet Questionnaire for screening pathological gamblers. Psychological Reports, 80, 83-88.

Kessler, R. C., Hwang, I., LaBrie, R. A., Petukhova, M., Sampson, N. A., Winters, K. C., et al. (2008). DSM-IV pathological gambling in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychological Medicine 38(9), 1351-1360.

LaPlante, D. A., Nelson, S. E., LaBrie, R. A., & Shaffer, H. J. (2008). Stability and progression of disordered gambling: Lessons from longitudinal studies. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 53(1), 52-60.

Petry, N. M., Stinson, F. S., & Grant, B. F. (2005). Comorbidity of DSM-IV pathological gambling and other psychiatric disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 66(5), 564-574.

Shaffer, H. J., LaBrie, R., Scanlan, K. M., & Cummings, T. N. (1994). Pathological gambling among adolescents: Massachusetts gambling screen (MAGS). Journal of Gambling Studies, 10(4), 339-362.

Toce-Gerstein, M., Gerstein, D., & Volberg, R. (in press). The NODS-CLiP: A rapid screen for adult pathological and problem gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies, epub ahead of print.