The WAGER Vol. 11(10) – What about the Youth? Revisiting Suicidality and Gambling

People with gambling problems are likely to suffer both financially and emotionally. In particular, studies have suggested that the severity of problem gambling is related to suicidality (Ledgerwood, Steinberg, Wu, & Potenza, 2005). The relationship between suicide and gambling is a complicated one, however. The WAGER has published several reviews of this topic. The recent two part series examined the methodological issues associated with assessing the relationship between gambling and suicidality (WAGER 10(8), 10(9)). However, the WAGER has not considered the relationship between youth gambling and suicidality. This relationship is particularly important to examine since both suicidality and problem gambling have been reported to be more prevalent among adolescents than adults (Dervic et al., 2006; Zangeneh, 2005). This week’s WAGER looks at a longitudinal study that closely examines youth gambling and suicidality (Feigelman, Gorman, & Lesieur, 2006).

Feigelman et al. used data from The National Longitudinal Survey of Adolescent Health. This survey included three waves. The investigators conducted the first wave between April and December 1995 with 18,910 children enrolled in grades 7 through 12. The second wave followed up a year later with 13,570 participants from the first wave. The third wave occurred six years after the second wave with 14,322 of the original participants. The participation rate was 80 % for Wave 1, 72 % for Wave 2, and 75% for Wave 3. In addition to multiple demographic and psychosocial variables, the participants completed two items about suicidality (i.e., “During the past 12 months have you ever seriously thought about committing suicide?” and “During the past 12 months how many times have you actually attempted suicide?”).

Participants also completed four items derived from DSM-IV criteria measuring lifetime gambling problems at Wave 3. Participants who endorsed any of the gambling problem items were classified as at-risk for lifetime gambling problems. The investigators measured the relationship between suicidality and gambling problems by conducting logistic regression analyses. The analyses set suicidality measures as the dependent variables, and at-risk for gambling problems and gender as independent variables.

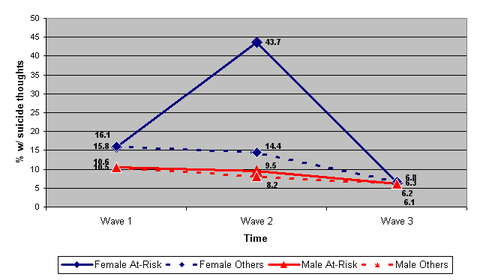

Figure 1: Suicide Thoughts Among Adolescents At-risk for Lifetime Gambling Problems(Adapted from Feigelman, Gorman, & Lesieur, 2006)

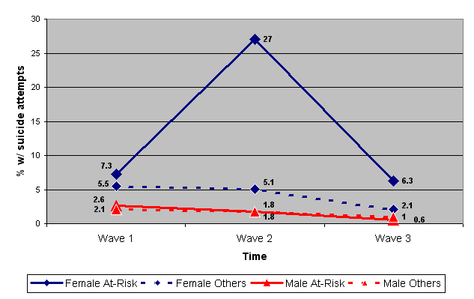

Figure 2: Suicide Attempts Among Adolescents At-risk for Lifetime Gambling Problems (Adapted from Feigelman, Gorman, & Lesieur, 2006)

Approximately 2% of the participants were at risk for lifetime gambling problems. The suicide attempt rate within the full sample ranged from 1.5% to 3.7% across waves, while the rate of suicidal thoughts ranged from 6.0% to 13.2%. The logistic regressions showed that problems with gambling were not directly related to suicidality at any wave (Wald .2s ranged from 0.00 to 0.47). However, as seen in Figures 1 and 2, female participants who were at-risk for gambling problems in Wave 3 (i.e., when they were between the ages of 20 and 24) were significantly more likely to think about or attempt suicide at Wave 2 (i.e., when they were in high school) compared with females who evidenced no risk for gambling problems. Male participants at-risk for gambling problems did not differ from males with no risk for gambling problems in their rate of suicidal thinking or attempts. Surprisingly, Feigelman, Gorman, and Lesieur (2006) found that male adolescents at-risk for gambling problems were more likely to be depressed than other males at all three waves; however, females at-risk for gambling problems were more likely to be depressed than other females only at Wave 3. Further analyses showed that differences in depression among females did not account for the observed relationship between at-risk for gambling problems and suicidality at Wave 2.

There are three salient limitations associated with this study. One limitation of this study is that the researchers only assessed the lifetime gambling measure during Wave 3. Participants might not have remembered accurately their past gambling behavior. Assessing gambling at a single time point makes it impossible to determine precisely how gambling and suicidality relate (i.e., whether one precedes or causes the other). Another limitation is that the investigators used a gambling measure based on only partial DSM-IV criteria. This limits their ability to compare their assessment of gambling disorder to other studies. Finally, as the authors noted, 96 participants died during the course of the study, but the cause of death was not available. It is possible that some of these missing cases represented successful suicide attempts. Thus, it is important to consider if these suicides were gambling related and or if other factors played a role.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, the current study found that gambling problems in general is not significantly related to suicidality among adolescents. However, the researchers did find a significant relationship between Wave 2 suicidality and lifetime gambling measured at wave 3 for female participants compared to the other groups. These results suggest that females who are suicidal might be more at risk for lifetime gambling problems; however, females with gambling problems are not at an increased risk for suicide. Future research needs to examine these discrepancies when examining the relationship between at-risk for gambling problems and suicidality across time; future studies also need to identify factors such as age that might influence this relationship. These findings can then better help both suicide intervention programs and gambling treatment programs to determine and help those most vulnerable to this potentially deadly interaction.

What do you think? Comments on this article can be addressed to Sarbani Hazra.

References

Dervic, K., Gould, M. S., Lenz, G., Kleinman, M., Akkaya-Kalayci, T., Velting, D., et al. (2006). Youth Suicide Risk Factors and Attitudes in New York and Vienna: A Cross-Cultural Comparison. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 36(5), 539-552.

Feigelman, W., Gorman, B. S., & Lesieur, H. (2006). Examining the Relationship Between At-Risk Gambling and Suicidality in a National Representative Sample of Young Adults. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 36(4), 396408.

Ledgerwood, D. M., Steinberg, M. A., Wu, R., & Potenza, M. N. (2005). Self-reported gambling-related suicidality among gambling helpline callers. Psychol Addict Behav, 19(2), 175-183.

Zangeneh, M. (2005). Suicide and gambling. AeJAMH (Australian e-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health), 4(1), 1-3.