Addiction & the Humanities Vol. 2(1) – Self-Portraits of a Struggle with Addiction: The Life and Paintings of Frida Kahlo

Frida Kahlo’s self-portraits convey the suffering she experienced during her turbulent life. Kahlo had a unique talent for translating her pain into artwork that elicits a visceral response from the viewer (Fuentes, 1995). However, rather than just a morose expression of her pain, her self-portraits also show beautiful and whimsical images which reflect her means of coping with painful experiences. Kahlo became addicted to multiple substances including opioids, alcohol, and cigarettes; the development of her addictive behavior and the nature of it remain elusive. This week’s Addiction and the Humanities explores the legacy of Frida Kahlo’s artwork and the factors in her life that might have contributed to her addictive behavior.

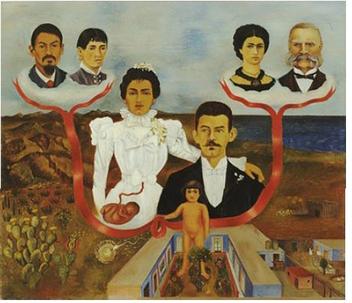

Kahlo grew up in Mexico City in the midst of the Mexican revolution. She was of mixed ancestry, her mother was a devout Catholic of indigenous Mexican and Spanish descent and her father was from Jewish, Hungarian descent. Kahlo illustrates her lineage in a painting entitled My Grandparents, Parents and I (family tree). She had a happy early childhood until the age of six when she contracted polio and spent an extended period of time in the hospital. Her right leg was deformed as a result of the polio and her classmates ostracized her because of the deformity calling her “pata de palo,” peglegged Frida (Bose, 2005). Kahlo recounts that this experience of being ostracized by classmates led her to develop dual identities so that other people would not know how much she was suffering: showing a strong, rebellious and defiant exterior and keeping her emotional and physical pain and weaknesses bottled up inside (Alcantara & Egnolff, 2001). At this point in her life, she also created an imaginary friend in a happier world she could visit through a windowpane in her bedroom. This shows Kahlo’s capacity for producing a creative response to a traumatic experience (Bose, 2005). However, this evasive style of coping with suffering and consequent isolation from social support might have been a key risk factor that influenced the development of her addictive behavior.

At the age of 18, Kahlo was the victim of a streetcar accident in which she was impaled by an iron rod, fracturing bones in her spine, ribs, pelvis and right leg. She was not expected to recover. Kahlo persevered, enduring multiple surgeries and wearing plaster corsets for months at a time She was eventually able to walk again, though she experienced pain for the rest of her life and suffered multiple miscarriages as a result of accident-related injuries (Fuentes, 1995).

After the accident, Kahlo taught herself how to paint during her hospital stay. She described her inspiration for painting when she said, “I paint my own reality. The only thing I know is that I paint because I need to” (Bose, 2005, p. 58). Painting was a way for her to express both her pain and her massive effort to endure the pain (Bose, 2005). The trauma of the accident and the chronic pain and infertility that she experienced could have been integral to her adoption of addictive behavior. Kahlo’s first exposure to opioids to treat her pain from the accident was iatrogenic. Her emotional vulnerability at the time of exposure to these drugs might have contributed to her eventual

opioid overuse and addiction.

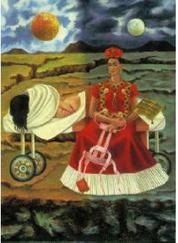

Kahlo maintained her dual identities after the accident. Her painting Tree of Hope Stay Strong vividly portrays Kahlo’s internal struggle between weak and strong identities. The left side shows her weak identity turned toward the Sun. The right side shows her strong identity at night with the moon. She portrays herself as brave, although a tear trickles down her cheek (Alcantara & Egnolff, 2001).

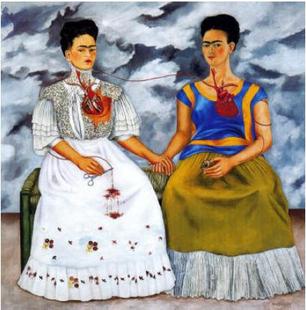

Although the images shown in Kahlo’s paintings show morbid aspects of her personality, Kahlo had many positive qualities that she displayed publicly. She was an outspoken political activist and artist during a time when women rarely participated in these matters. She was described by her contemporaries as charming and as having a boisterous sense of humor. However, her turbulent relationship with her husband Diego Rivera was a stressor that took a toll on her mental well-being. Kahlo once said, “I suffered two grave accidents in my life. One in which a streetcar knocked me down…the other was Diego” (Alcantara & Egnolff, 2001, p.34). Kahlo was emotionally dependent on Rivera and was devastated when he suggested they get a divorce. Kahlo expressed her distress over her separation from Rivera in one of her most well-known paintings, The Two Fridas. This painting is another illustration of the struggle between her dual identities: the stronger identity shown in the painting dressed in traditional Mexican costume possesses her heart and holds a small cameo of Rivera in her left hand, and the weaker identity dressed in European costume has a paler complexion and her heart cut out. Clearly, Kahlo felt that she did not have a strong identity unless she was with Rivera (Alcantara & Egnolff, 2001). She remarried Rivera despite his multiple extramarital affairs, including one with her sister Cristina. Kahlo experienced recurrent depression and continued to use drugs and alcohol as an attempt to escape from her suffering.

Kahlo maintained her strength of mind throughout multiple surgeries and emotional ordeals. She described how she felt during this period of her life when she said, "I am not sick. I am broken. But I am happy as long as I can paint” (Fuentes, 1995, p. 23). However, as she succumbed to her addiction and sank deeper into depression, she painted only still life. Several of Kahlo’s biographers have suggested that the still lives were self-portraits that symbolized her extreme state of depression (Alcantara & Egnolff, 2001; Fuentes, 1995). Her last painting, Viva La Vida, Watermelons, shows watermelon cut open like a wound. The inscription “Long Live Life” represents both her desire to leave behind a legacy and her imminent death. Kahlo died at the age of 47. It is suspected that her death was a suicide from a morphine overdose (Fuentes, 1995).

A recent New York Times article (Allam, 2005) discusses the use of Kahlo’s paintings as a catalyst for patients to express their emotions about painful experiences. In particular, this treatment was developed as a culturally sensitive therapy for women of Mexican descent. The article reiterates patients’ claims that these images resonate with their own experiences, help them to feel more comfortable discussing their emotions, and inspire them to improve their lives (Allam, 2005). Ironically, Kahlo never used her artwork in this way: she maintained a disconnect between the presentation of her true feelings in her artwork and how she interacted with other people in the world; perhaps if she had expressed her suffering more openly with other people, she might have dealt with her problems in more constructive ways (i.e. rather than drug overuse and addiction), and led a longer and happier life.

What do you think? Comments can be addressed to Allyson Peller.

References

Alcantara, I., & Egnolff, S. (2001). Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. London: Prestel.

Allam, A. (2005, July 14, 2005). When Art Imitates Pain, It Can Help Heal, a Therapy Group Finds. The New York Times.

Bose, J. (2005). Images of Trauma: Pain, Recognition, and Disavowal in the Works of Frida Kahlo and Francis Bacon. Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis & Dynamic Psychiatry.

Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis & Dynamic Psychiatry J1 -Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis & Dynamic Psychiatry, 33(1), 51-70.

Fuentes, C. (1995). Introduction. In The Diary of Frida Kahlo: An Intimate Self-Portrait (pp. 7-24). New York: Abradale Press.