The WAGER Vol. 10(10) – Risky Business: Youth Gambling

Websites, radio commercials, and television coverage, increasingly are exposing adolescents to gambling and the potential problems that can accompany gambling. However, there are other factors besides media exposure that influence the development of gambling among youth. Several of these factors are also relevant to developing other risky behaviors (e.g., drug use). Studies have shown, for example, that parents and peers play an important role in children’s risk for potential problem behaviors like underage gambling (Vachon, Vitaro, Wanner, & Tremblay, 2005; Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Rohde, & Seeley, 2004). Currently, many researchers are studying whether some of these factors are more risky than others in stimulating various risky behavior patterns. This week’s WAGER reviews Barnes, Welte, Hoffman, & Dintcheff’s (2005) examination of predictive factors for underage gambling and other risky behaviors among youth.

Barnes et al. (2005) conducted two separate longitudinal studies measuring family, peer, and individual risk factors for various risky behaviors. The first study surveyed adolescents (age 13-16 at first assessment) and their parents six times at yearly intervals between 1989 and 1994. There were 226 male and 296 female adolescent participants, 29% of whom were Black and 71% of whom were either White or of another race. The second study examined delinquency among 625 young male participants (49% Black, 51% White or ot1her, age 16-19 at first assessment) living in high crime-rate neighborhoods assessed three times at 18-month intervals between 1992 and 1996. The researchers assessed the following risky behaviors: underage gambling, alcohol misuse, illicit drug use, and delinquency. Youth answered questions about demographics (i.e., age, race, mother’s education) parental monitoring, peer delinquency, and their own impulsivity and moral disengagement (i.e., amount of guilt felt if engaged in various delinquent acts). This review will only report findings of Study 2; we expect the risky behavior levels to be higher for this study because the sample derives from high-crime neighborhoods.

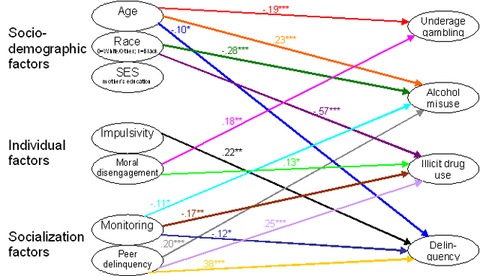

Figure 1 summarizes the model and the significant results that were generated by using structural equation modeling. The authors included risk factors from the first assessment, when youth were between age 16 and 19, and outcome measures from the second assessment, 18 months later, in their model. The numbers in the model (i.e., standardized path coefficients) indicate the relationship between each risk factor and each outcome, controlling for all other variables in the model. For example, parental monitoring is negatively associated with illicit drug use, while taking other predictors like impulsivity into account. For gambling, age was a significant predictor. The older youth were at the first assessment, the less they reported gambling at follow-up. Moral disengagement also was significantly associated with gambling. The less guilty youth felt about conducting delinquent acts, the more they reported gambling. Unlike gambling, which had only two predictors, alcohol misuse, illicit drug use, and delinquency had multiple predictors from all three domains (i.e., individual, socio-demographic, and socialization factors). Strikingly, both parental monitoring and peer delinquency successfully predicted alcohol misuse, drug use, and delinquency, but not gambling. (1)

Figure 1: Partial Correlations of Predictors of Gambling, Alcohol Misuse, Drug Use, & Delinquency

p < .05. **p <.01. ***p<.001.

There were some limitations to the study. The researchers grouped White participants with participants from other races. These racial groupings could have influenced the extent to which race was associated with gambling. These issues are important to consider when examining race as a predictor. Another limitation is that scores on the outcome behaviors were described as low, and those scores were not reported. If most participants did not engage in the risk behaviors, then the study might not be a fair assessment of the predictors of these behaviors. Finally, the researchers examined gambling behaviors, not gambling problems; gambling is not the same as having a gambling problem. For example, participating in gambling does not necessarily indicate a problem behavior to the extent that misusing alcohol does (i.e., binge drinking). This might account for the lack of findings.

This study demonstrates the necessity of carefully examining multiple predictors and risky behaviors among youth simultaneously. By studying risk factors and outcomes in this way, the results help to distinguish, for example, the predictors that are relevant to gambling compared to other risky behaviors. It is important to note that gambling had fewer predictors than the other behaviors. This might occur if the frequency of gambling is low compared to other behaviors, however, it also is possible that parents might not be as concerned with gambling as with alcohol and other drug use. Similarly, peers might not be as influential in encouraging adolescent gambling practices as they are in stimulating adolescent substance use.

Barnes et al. successfully demonstrated that some personal characteristics, such as moral disengagement, did predict gambling among male adolescents in this sample. Thus, future research might examine additional psychological characteristics and how these relate to gambling, as compared to other risky behaviors, among adolescents. In addition, future studies ought to apply this risk factor model to the longitudinal prediction of gambling problems in young adulthood, examining the relationship between the risk factors, adolescent gambling, and young adult gambling problems.

Notes

1. Study 1 showed similar directional patterns (e.g., more peer delinquency, not less, predicted more delinquency) and replicated some, but not all, of the significant findings for males. Overall, alcohol misuse, drug use, and delinquency had more risk factor predictors than gambling, just as in the reviewed study, and peer delinquency and parental monitoring were significant predictors of multiple risky behaviors. However, delinquent behavior was only predicted by demographic factors, and gambling had no significant predictive factors.

What do you think? Comments on this article can be addressed to Sarbani Hazra.

References

Barnes, G.M., Welte, J.W., Hoffman, J.H., & Dintcheff, B.A. Shared Predictors of Youthful Gambling, Substance Use, and Delinquency. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 19(2), 165-174.

Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J., Rohde, P., & Seeley, J.R. (2004). Individual, family, and peer correlates of adolescent gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies, 20(1), 23-46.

Vachon, J., Vitaro, F., Wanner, B., & Trembla, R.E. (2004). Adolescent gamblingrelationships with parent gambling and parenting practices. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 18(4), 398-401.