The DRAM, Vol. 1(4) – Treating co-occurring alcoholism and depression

National studies show that alcoholism and depression frequently co-occur (Kessler, Crum, Warner, Nelson, Schulenberg, Anthony, 1997). Each problem poses significant emotional, financial, and social costs to families and society. Though there are effective treatments for either health crisis alone, treating co-occurring depression and alcoholism might require more than simply combining effective individual approaches to each disorder. This week The DRAM focuses on a study by Moak, Anton, Latham, Voronin, Waid, and Durazo-Arvizu (2003) that assessed the effectiveness of sertraline, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), for treating drinking and depression, when added to Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT).

Moak et al. (2003) recruited through newspaper advertisement or clinical referral 240 treatment seekers meeting Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 1987) criteria for major depressive episode or dysthymia and alcohol dependence or abuse. The authors employed extensive exclusion criteria, including psychoactive substance dependence. Of 240 potential participants, 185 were seen for an initial assessment; 78 were excluded from the study, and 107 agreed to participate. Moak et al. (2003) asked these individuals to remain alcohol abstinent for the 3 days prior to initiation of a single-blind placebo condition. All subjects had an individual CBT session during the placebo lead-in week. Individuals who remained abstinent or only drank minimally for an additional 7 days and scored at least a 17 on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D, 21 items — Hamilton, 1960) were randomized into SSRI or placebo groups in a double-blind design. All participants received 4 tablets of study medication: either sertraline or matched placebo. The SSRI group started at 50 mg daily and gradually increased to 200 mg daily over two weeks. Dosage decreased back to 50 mg over 7 days and stopped before the end of the 12 week study. Researchers recorded alcohol and depression-related data during the 12 weeks. Evaluations were conducted at the end of the study, week 12, and at follow-up, weeks 16 and 26 (post-treatment); Moak, et al, will present follow-up data in another article that is yet to be published. Any participants who dropped out of the study during the 12 week treatment period, were encouraged by researchers to return for follow-up evaluations at weeks 12, 16, and 26. Approximately 70% of the participants completed the study, with participants on SSRI more likely (p = .08) to complete the study (84%) than those on placebo (67%).

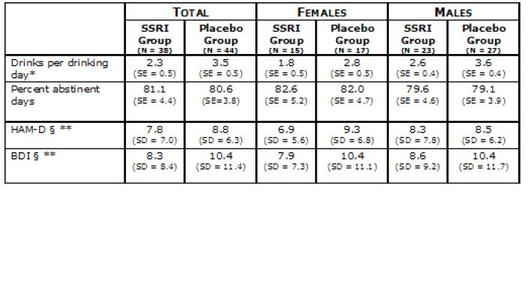

Figure. Drinking and depression outcome measures (adapted from Moak et al., 2003). BDI=Beck Depression Inventory

* Significant difference, p<0.05 between SSRI and placebo groups; § significant difference for females only

** Score given at last available treatment.

The results indicate that CBT supplemented with administration of sertraline reduces drinks per drinking day to a greater extent than CBT supplemented placebo; participants in both groups had fewer drinks per drinking day and more percent days abstinent during the study than in the 90 days prior. Further, there was no difference between the sertraline and placebo groups with regard to heavy drinking days per week, or percent days abstinent. The authors note that the SSRI used in this study might be more beneficial for women than men, as significantly greater changes in depression for the sertraline group were observed only for women. Depression and drinking generally decreased for both SSRI and placebo groups over the course of the study.

It is important to note that the CBT used for this study is a truncated version designed by Project MATCH (Kadden, Carroll, Donovan, et al., 1992). The results of the Project MATCH study show that condensed CBT is effective in treating people who are alcohol dependent and depressed. Overall, though sertraline resulted in participants drinking fewer drinks per day, other drinking outcomes did not differ greatly between the two groups. It will be interesting to see the results of the data collected during follow-up visits at 16 and 26 weeks. This will hopefully help determine the long-term efficacy of these treatments.

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (1987). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, third edition (revised) (Third (revised) ed.). Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association.

Hamilton, M. A. (1960). A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 23, 56-62.

Kadden, R., Carroll, K., Donovan, D., et al. (1992). Cognitive-behavioral coping skills therapy manual: A clinical research guide for therapists treating individuals with alcohol abuse and dependence (Vol. 3). Washington, DC.

Kessler, R. C., Crum, R. M., Warner, L. A., Nelson, C. B., Schulenberg, J., & Anthony, J. C. (1997). Lifetime cooccurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 54, 313-321.

Moak, D. H., Anton, R. F., Latham, P. K., Voronin, K. E., Waid, R. L., & Durazo-Arvizu, R. (2003). Sertraline and cognitive behavioral therapy for depressed alcoholics: Results of a placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 23(6), 553-563.