The WAGER, Vol. 6 (49) – Problem and Non-Problem Gambling Adolescent Marijuana Abusers: Non-gambling Risk Behaviors Part II

A previous WAGER highlighted problem gambling among adolescents as an important issue. High prevalence rates among adolescents (Shaffer, Hall, & Vanderbilt, 1999) confirm this importance. The current WAGER is the second in a two-part series that reports on how the gambling pathology of substance abusers is associated with other potentially harmful behaviors. Last week’s WAGER reviewed a study by Petry (2000) that explored HIV-risk behaviors among adult substance abusers. In this WAGER, we review a study conducted by Petry and Tawfik (2001) that explored illegal and risky sexual behavior among adolescent marijuana abusers.1

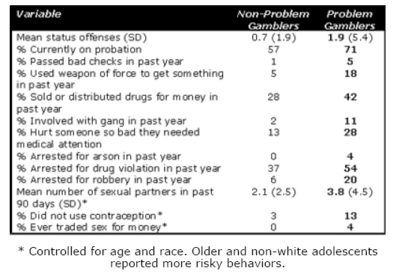

A total of 255 marijuana-abusing adolescents (aged 12-18 years) recruited from the Hartford, Connecticut and the Philadelphia, Pennsylvania sites of the Cannabis Youth Treatment Project participated in this study. Researchers used the Global Assessment of Individual Needs (GAIN; reviewed in Petry & Tawfik, 2001) to collect data pertaining to substance use, illegal behaviors, psychiatric comorbidity, gambling, and risky sexual behavior.2 Individuals were grouped as either Problem (n=198; endorsement of one or more DSM gambling symptoms) or Non-Problem Gamblers (n=57; endorsement of no DSM gambling symptoms).3 Petry and Tawfik (2001) used multivariate analyses, X2 and univariate analyses to explore differences between problem and non-problem gambling adolescents. The statistically significant differences between problem and non-problem gamblers for illegal and risky sexual behaviors are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Illegal and sexual behaviors among non-problem and problem gambling adolescent marijuana abusers

The results of the Petry and Tawfik (2001) study indicate that, among marijuana-abusing youths, having one or more problems due to gambling is significantly related to increased HIV-risk behavior. Marijuana-abusing adolescents with one or more gambling problems were also more likely to have engaged in illegal activities or come into contact with the criminal system. This study includes findings that might support the view that problem gambling is part of the family of impulse control disorders.

Some limitations exist. The study is limited to adolescent marijuana abusers in two locales and the findings may not generalize to a larger population. Also, it would have been informative to explore tendencies to engage in risky behaviors for pathological gamblers, as opposed to problem gamblers. The number of pathological gamblers in the sample, however, was too small for this analysis. Future research should devote more effort to gaining a large enough sample to obtain sufficient statistical power to conduct meaningful analyses for these groups. Importantly, related research on male non-substance abusing college-age gamblers has found that South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS; Lesier & Blume, 1987) scores were associated with measures of impulsivity, risky behavior, and sensation seeking for non-pathological, but not pathological gamblers (Langewisch & Frisch, 1998). Thus, these results might not generalize well to those with the most severe problems.

Despite these considerations, the Petry and Tawfik study advances our knowledge and makes an important contribution to the scientific literature. This study includes a dimension, problems due to gambling, that is not often included in the analysis of risk behavior among substance-abusing adolescents. In addition, this research suggests that the presence of gambling problems is a potentially important factor to consider when developing effective treatment programs for substance-abusing youths.

Notes

1 The study also examined differences in substance abuse and psychiatric comorbidity between problem and non-problem gamblers.

2 Exclusion criteria: acute psychological or medical condition, history of severe or violent behavior, non-English speaking, alcohol use for more that 45 days in the last 90 and heroin or cocaine use for more than 13 of the last 90 days.

3 Eight individuals met DSM-IV criteria for pathological gambling, i.e., five or more problems. These individuals were included in the problem gambling group.

References

Langewisch, M. W. J. & Frisch, G. R. (1998). Gambling behavior and pathology in relation to impulsivity, sensation seeking, and risk behavior in male college students. Journal of Gambling Studies,14(3), 245-262.

Lesieur, H. & Blume, S. (1987). The South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS): A new instrument for the identification of pathological gamblers. American Journal of Psychiatry, 144, 1184-1188.

Petry, N. M. (2000). Gambling problems in substance abusers are associated with increased sexual risk behaviors. Addiction, 95(7), 1089-1100.

Petry, N. M. & Tawfik, Z. (2001). Comparison of problem-gambling and non-problem-gambling youths seeking treatment for marijuana abuse. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(11), 1324-1331.

Shaffer, H. J., Hall, M. N., & Vanderbilt, J. (1999). Estimating the prevalence of disordered gambling behavior in the United States and Canada: A research synthesis. American Journal of Public Health, 89, 1369-1376.

The WAGER is a public education project of the Division on Addictions at Harvard Medical

School. It is funded, in part, by the National Center for Responsible Gaming, the

Massachusetts Department of Public Health, the Addiction Technology Transfer Center of

New England, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and the

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment.