The WAGER, Vol. 6 (40) – Changing Your Mind in 28 Days

Last week’s WAGER reported on a study suggesting that the effectiveness of a gambling treatment program need not be defined by abstinence from post-treatment gambling. This week’s WAGER reviews a study that suggests that the effectiveness of a gambling treatment program does not need to be evaluated by posttreatment gambling behavior. Breen, Kruedelbach, & Walker (2001) evaluated the success of a cognitive-behavioral-therapy (CBT) gambling treatment program by changes in gamblers’ beliefs and attitudes about gambling.

Study participants were 66 veterans (64 men; 2 women) who were admitted to a CBT inpatient treatment program between October 1998 and June 1999 at a Veterans hospital in Ohio. During this 28day program, patients received individual, group, and educational treatment. Classes and discussions focused on irrational beliefs and attitudes toward gambling. At admission and discharge, study participants completed the Gambling Attitude and Beliefs Survey (GABS; described in Breen et al., 2001), a measure of gamblers’ irrational beliefs and positive attitudes toward gambling. Higher scores on this survey indicated greater agreement that “gambling is felt to be exciting and socially meaningful and that luck and strategies (even illusory ones) are important.” Participants also completed the South Oaks Gambling Screen (Lesieur & Blume, 1987) and the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979). The WAGER discusses findings concerning the GABS.

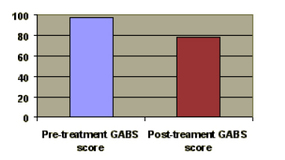

A paired sample t-test showed a significant decrease in GABS scores from admission to discharge (t(55)=7.82, p<0.01). Thus, after treatment, participants reported a reduction in irrational beliefs and positive attitudes towards gambling.

Figure 1: Mean GABS Scores Pre- and Post-treatment

Some limitations exist in this study. First, the small number of participants in this study were all inpatients, all veterans, and overwhelmingly male. This might restrict the generalizability and stability of this study. Second, although the authors recognize that demand characteristics, situational pressures that influence individuals’ natural patterns of behavior, might play a role in the participants’ self-reports, this possibility is downplayed. It is likely, for example, that participants’ probable need to please treatment providers significantly influenced their reported liking for gambling (positive attitude) and irrationality of beliefs. The short time period between treatment and evaluation prevents avoiding this issue. Changing attitudes can be a long and arduous process and fleeting changes may easily masquerade as lasting changes. Kelman (1958) reports three points of attitude change: compliance, identification, and internalization. Specifically, if individuals are compliant, they engage in actions/attitudes for externally motivated reasons (e.g. a pathological gambler won’t gamble because his therapist said not to gamble). Individuals who identify engage in actions/attitudes because of a desire to belong (e.g. a pathological gambler won’t gamble because he doesn’t want to disappoint his therapist). The most durable of all, internalization, comes when individuals engage in actions/attitudes for no reason but the action/attitude itself (e.g. a pathological gambler has no desire to gamble). It is unclear whether the participants in this study are compliant, identified, or if they have internalized new attitudes about gambling. If attitude change is to be a significant and important measure of treatment effectiveness, it is important to determine the extent to which an attitude is actually changed.

The work of Breen et al. (2001) is notable because it is the first empirical study to report that the way a gambler thinks about gambling is altered by treatment. Thus, changes in cognition concerning gambling could help to determine how well a gambling treatment program works. The need for new methods of evaluation increases with the emergence of new types of treatments. Breen et al. (2001) provide insight into one potential method of evaluation. A universal assessment tool, which incorporates multiple methods of evaluation, might keep up with the proliferation of new gambling treatment programs.

References

Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, B. (1979). Cognitive Therapy of Depression. New York: Guilford Press.

Breen, R. B., Kruedelbach, N. G., & Walker, H. I. (2001). Cognitive changes in pathological gamblers following a 28-day inpatient program. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 15(3), 246-248.

Kelman, H. C. (1958). Compliance, identification, and internalization: Three processes of attitude change. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 2, 51-60.

Lesieur, H. R. & Blume, S. (1987). The South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS): A new instrument for the identification of pathological gamblers. American Journal of Psychiatry, 144, 1184-1188.

The WAGER is a public education project of the Division on Addictions at Harvard

Medical School. It is funded, in part, by the National Center for Responsible

Gaming, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, the Addiction

Technology Transfer Center of New England, the Substance Abuse and Mental

Health Services Administration, and the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment.