The WAGER Vol. 5(49) – They Don’t Eat Quiche, But They Like Dogfighting

Research suggests that in the southern region of the United States men widely subscribe to a traditional gender role that emphasizes masculinity in terms of aggressiveness, competitiveness and strength (Hurlbert & Bankston, 1998; O’Neil, 1982; Hantover, 1978). A study conducted by Evans, Gauthier and Forsyth (1998) argues that this masculinity is often associated with dogfighting, a highly competitive gambling sport illegal in all fifty states. More fittingly, within the context of gambling disorders, this research points to the importance that studies of cultural influence might play in helping to explain the emergence and maintenance of problem and pathological gambling.

Data collected in Louisiana and Mississippi from interviews conducted with men who fight dogs for sport (n=31) as well as ethnographic observations from fourteen dog fights and pre-fight meetings indicate that dogs employed for dogfighting are the means by which some of their owners develop, express and validate their masculinity (Evans et al., 1998). Indeed, through their dog’s fighting prowess, dogfighters attain status as true dogmen. Specifically, the rules of dogfighting dictate dogs that show "gameness," or, as dogmen consider it, "an awesome persistence that flows from an invincible will" (Jones, 1988, p. 249), reflect positively on their owner. Dogmen consider that dogs with gameness express masculine characteristics in the fight (i.e., aggressiveness, competitiveness, and strength). These characteristics, in turn, are ascribed to their owner, bringing him status and prestige within the dogfighting subculture (Evans et al., 1998).

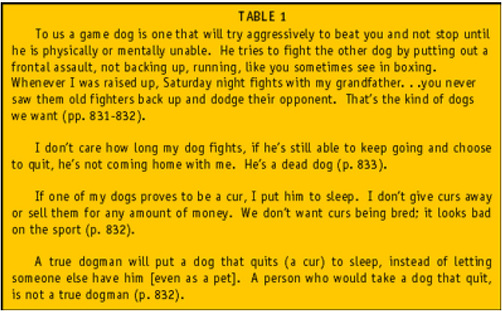

If, however, a dog shows signs of cowardice (i.e., a low threshold for pain and an inclination to quit the fight), the animal is dubbed a "cur." Dogmen perceive cur dogs as humiliating for men who own them. As a result, curs are killed. In a sport that symbolizes masculinity, according to Evans et al. (1998), there is no place for cowards. Table 1 illustrates statements from dogmen that support the conclusions of Evans and her associates.

While the research conducted by Evans et. al. (1998) is arguably sociologically significant, it does not address what might be a cultural and causal relationship between dogfighting, masculinity, and gambling among betting spectators1. Indeed, there is arguably a culture of masculinity that influences both the dog fighting and gambling that accompanies it. Theoretically, this culture of masculinity seeks to distribute masculine honor and status more than monetary gain. It creates an environment within which bettors consider winning money as important, but solidarity and respect from peers is paramount.

Like dogmen, betting spectators are usually men who have previously or soon will fight dogs in competition (Evans et al., 1998). Within dog fighting subcultures, bettors are likely to wager based upon their perception of a dog’s representation of traditional masculine traits rather than on logical and educated deductions regarding the dog’s chances to actually win the dogfight. Indeed, a gambling spectator who wrongly bets on a "cur" dog might be perceived as less of a man-similar to the cur’s owner-since the betting spectator failed to recognize the dog’s weaknesses, perhaps indicating to others within the close-knit dogfighting subculture the bettor’s lack of masculine traits.

On the contrary, a spectator who bets on a dog with "gameness" is perceived as masculine (similar to the dog’s owner). If a dog exhibits aggressiveness, competitiveness, strength and the will to never quit, but is defeated in the fight, some gamblers might lose money, but none will lose respect for their masculinity.

Although the causal associations between dogfighting, masculinity and gambling are still hypothetical, this area of research reflects important considerations with regard to the influence that gambling behavior within dogfighting subcultures has on those who participate in such activities. In addition, this research can clarify to what extent a connection between dogfighting, masculinity, and gambling exists and the comparative strength of this connection in dogfighting cultures throughout the United States.

The considerations raised by studies of cultural influence on gambling are vitally important to understanding the very nature of disordered gambling. For example, if less emphasis is placed on winning money and more on picking a masculine dog, win or lose, can habitual dogfighting-only gamblers still develop into problem or pathological gamblers? Moreover, if those who gamble on dogfights also gamble at other gaming venues like casinos and horse tracks, to what extent does their desire to meet traditional and culturally predetermined masculine ideals influence the extent of their gambling? Future research on gambling needs to address these questions since an improved understanding of these influences might reveal the very nature of gambling disorders.

[1] The reader should note that this is not a criticism of Evans et al. (2000), as the examination of this possible relationship was never identified as part of the study’s original research hypotheses.

References

Evans, R., Gauthier, D.K., and Forsyth, C.J. (1998). Dogfighting: Symbolic expression and validation of masculinity. Sex Roles, 39(11/12), 825-838.

Hantover, J. P. (1978). The Boy Scouts and the validation of masculinity. Sociological Issues, 34, 184-195.

Hurlbert, J. S. and Bankston, W.B. (1998). Cultural Distinctiveness in the Face of Structural Transformation: The "New" Old South. In D. R. Hurt (Ed.), Social Change in the Rural South: 1945-1995. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

Jones, M. (1988). The Dogs of Capitalism Book I: Origins. Cedar Park, TX: 21st Century Logic.

O’Neil, J. M. (1982). Gender role conflict and strain in men’s lives. In K. S. N. B. Levy (Ed.), Men in Transition: Theory and Therapy. New York: Plenum Press.