The WAGER Vol. 5(16) – The Right Stuff: Options in Certification

Not so long ago, anyone possessing a limited knowledge of human anatomy (and, perhaps, a jar of leeches) could practice medicine. As the field developed, the prerequisites for becoming a doctor increased dramatically. Later, these prerequisites were standardized so that patients could expect every practitioner to have achieved a uniform level of knowledge and skill. Today, in the United States, medical education can last seven years or more, and students must meet certain national standards. Although the burden on doctors-to-be has multiplied, the benefits for the public are great. How many of us would choose a doctor who did not have an MD degree?

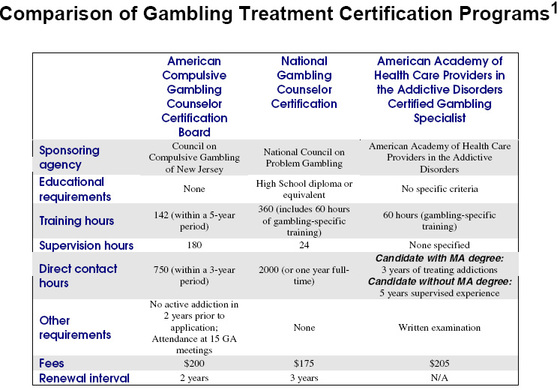

The history of training gambling treatment specialists has followed a course similar to that of general medicine. Within a short period of time, state and national organizations created certification programs to train and accredit healthcare providers in the treatment of addiction disorders. For pathological gambling alone, there are three certification programs which vary in criteria and degree of rigor. The requirements for each certificate are presented in the table below.

One interesting criterion is unique to the New Jersey program: specialists must be free from addictive disorders during the two years prior to application. There is a school of thought in addiction studies that believes that once one is diagnosed with an addictive disorder, it is impossible to be completely "free" from it for any period of time.

Another school of thought views pathological gambling as a purely medical condition no different from diabetes, asthma, or any other chronic disorder. Extending this paradigm, the question arises: Would we disqualify a medical student with a recent history of asthma from a pulmonary training program?

Does the field really need three individual certification programs? Might healthcare consumers be better served if providers were trained in accordance with a single standard? Which, if any, of the three training programs actually improves a practitioner’s ability to treat pathological gamblers? These questions can be answered only through systematic evaluation.

References

1Indiana Gambling Impact Study Commission (1999). Report to the Governor: The social, fiscal, and economic impacts of legalized gambling in Indiana. Indianapolis: Indiana University.