The WAGER Vol. 5(7) – Double Down: A Review

Half confessional and half family psychohistory, Double Down (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1999) describes itself as "reflections on gambling and loss." The protagonists and narrators are brothers Frederick and Steven Barthelme. The similarities between the two brothers, however, extend beyond the mere sharing of DNA. Both are accomplished writers, academics… and problem gamblers.

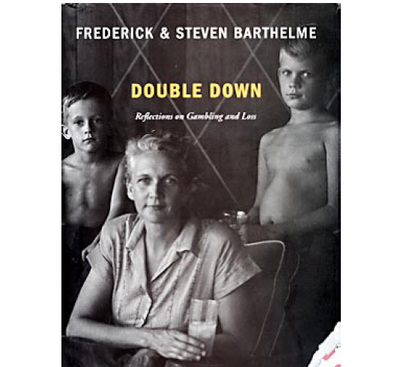

Following the death of their mother (pictured on the cover), the Barthelmes started making regular trips to the Mississippi coast casinos. They would play blackjack all night long, arriving home in time to tend to their job responsibilities. Within a period of roughly two years, their combined losses reached $250,000 – a sum which included a significant part of their inheritance. Their troubles worsened in 1997, when they were charged with the felony of conspiring with a blackjack dealer to defraud the casino.

The prose of Double Down is clean, simple, and direct hardly surprising, given the literary backgrounds of the authors. They speak of their behavior in terms that will be familiar to clinicians who have treated problem gambling or the addictions in general. The brothers see their monetary gains and losses as incidental to their pathology; rather, they are enticed by the feeling of gambling and the "aesthetic" of the casino floor.

But the narrative fails to address a fundamental question: Do the Barthelme brothers suffer from the disorder of pathological gambling? While they never doubt that their suffering is a direct result of their gambling, they never claim to have a psychiatric disorder. Nor do they ever report undergoing clinical evaluation. However distressing the consequences of gambling may be, they, alone, are insufficient to

diagnose the disorder. This logical quandary extends beyond the bounds of pathological gambling and is important in psychiatry in general.1

Their all-night, marathon gambling sessions might suggest the presence of mania. Furthermore, the Barthelmes never seem to lose control completely over their gambling. It is also interesting to note that the statistical probability of two brothers developing a low-prevalence disorder simultaneously is very small. The Barthelmes themselves seem reluctant to frame their behavior in the framework of psychiatry. While the authors speak freely of "addiction," they fail to elevate its significance beyond the level of jargon.

Readers seeking a book about the construct of addiction will be disappointed with the tale told by the Barthelmes. But for those seeking insight into problem gambling behavior, Double Down will be a delight to read. The narrative is lively and compelling, and the story is as intriguing as a mystery novel or other work of fiction – but there is nothing fictional about the suffering of Steve and Rick Barthelme.

Winning is better than losing, but neither is the goal of gambling, which is playing. Losing never feels like the worst part of gambling. Quitting often does.(p.121)

References

Barron, J., ed. (1998). Making diagnosis meaningful: Enhancing evaluation and treatment of psychological disorders. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association.