The WAGER Vol. 5(6) – “Count Me Out:” Missouri’s Voluntary Exclusion Program

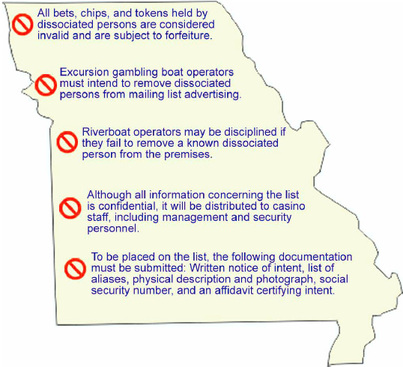

Bounded by two of America’s largest waterways and located in the heart of the nation, Missouri is home to an understandably popular riverboat casino industry. Since the legalization of riverboat gambling, Missouri has taken several steps to help treat and prevent pathological gambling and a permanent fund to support treatment efforts has been established in its Department of Mental Health. One of the more innovative of these measures is the creation of a "voluntary exclusion" law. The provisions of this rule allow problem gamblers to add themselves voluntarily to a statewide list of "dissociated persons." Persons on this list agree to avoid riverboat casinos. Violators of this self-ban are guilty of criminal trespassing, a crime which carries a penalty of up to six months of imprisonment. Voluntary exclusion is irreversible; once a person is added to the list, removal is impossible. Additional provisions of the law are listed below:

It is particularly interesting that voluntarily excluded individuals cannot remove themselves from the list once added. According to the law itself, this policy of irreversibility is based on "the belief that dealing with a gambling problem requires lifetime treatment and that a person is continuously recovering from a gambling addiction." (11 CSR 45-17.050 {1}) Given the paucity of evidence on the natural history of pathological gambling, such a belief should be tested empirically.

According to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch1, over 1,229 persons have voluntarily excluded themselves from gambling in Missouri. Is the popularity of the program a testament to its efficacy? Not necessarily. The policy does not ban dissociated persons from participating in the lottery or other forms of gambling, licit or illicit. The "Show-Me" state should be commended for its proactive attitude toward compulsive gambling. However, before the efficacy and impact of the voluntary exclusion program can be determined, it should be evaluated scientifically.

References

Young, V. & Bell, K. (2000, February 6). Often dismissed as being weak, compulsive gamblers may have a brain malfunction. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch, p.A10 [available online at http://www.post-dispatch.com/postnet/specialreports/gambling.nsf]