The WAGER, Vol 4(28) – Gambling & Suicide: A Study of 44 Cases

There is certainly no paucity of research on gambling and suicide. Numerous studies have produced a plethora of statistics, both supporting and denying a relationship between the two phenomena. Yet the entire story has yet to be told, for behind each statistic is the unique story of an individual in grave distress. Blaszczynski and Farrell (1999) take an important step in excavating these stories from the data sets and provide insight into the phenemonology of suicide.

Retrospective archival research poses many methodological difficulties, particularly when the subject is sensitive. In an attempt to avoid social stigma and financial consequences, there may be a tendency to under- or misreport suicides. Furthermore, if the death occurred without witnesses, the deliberate taking of one’s own life may be classified as accidental on the vital records that are so critical to research of this kind. And explicit suicide notes are not always left. Despite these difficulties, the authors set out to study suicide and gambling in the Australian State of Victoria.

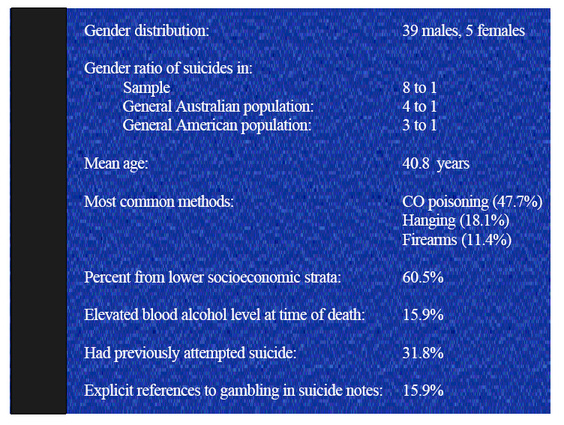

Their research began in the State Coroner’s Office, where they identified suicides occurring between 1990 and 1997. Only records in which gambling was mentioned were selected, creating a sample of 44 cases. Although the contents of case files varied, they generally included autopsy results, police reports, interviews with friends and family of the decedent, a history of any psychopathology and previous suicide attempts, suicide notes, and other documents relevant to the case. Findings gleaned from the review of these records are presented in the table below.

Of the suicide notes available for analysis, seven specifically mentioned a gambling problem. An eighth note attributed causation to a financial crisis caused by excessive gambling. It should be noted that not enough information was available to diagnose the decedents as pathological gamblers according to DSM-IV criteria. Other common stressors experienced by the sample included problems with relationships and difficulty with money. Personality traits common to many of the 44 cases include low self-esteem and introversion.

Noting the methodological difficulties associated with a descriptive study of this type, the authors find no conclusive evidence that gambling was "the major or sole contributing risk or predictive factor to the suicide." However, they find "sufficient indicators to provide strong support for the argument that gambling acted as a catalyst or played a relevant role in the suicide." They cite the case of a 34-year-old male found hanging in his garage. His loss of $13,000 to gambling had created tensions in his marriage. In the two weeks preceding the suicide he lost at least another $1,740 in casinos, leaving him with an account balance of $7.00 on the night of his death. However, his file also mentions stress at work, a failure to be promoted, and family discord. The data does not indicate whether these other factors were connected with the decedent’s gambling. Was gambling the major factor leading to his suicide? It is cases such as this one that make questions like these so hard to answer.

Source: Blaszczynski, A. & Farrell, E. (1998) A case series of 44 completed gambling-related suicides. Journal of Gambling Studies, 14(2), 93-109.

The WAGER is funded, in part, by the Massachusetts Council on Compulsive Gambling, the Andrews Foundation, and the National Center for Responsible Gaming.