The WAGER, Vol. 3(19) – Impulsiveness and problem gambling

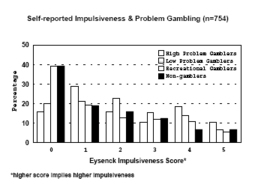

One of the challenges of research is interpreting associations. For example, finding an association between impulsiveness and pathological gambling among a sample does not necessarily provide information about which phenomenon preceded the other. Being impulsive may increase vulnerability to developing gambling problems, gambling problems could facilitate impulsiveness, or a third phenomenon could bring about both impulsiveness and pathological gambling. The primary study design that allows for a look at these temporal questions is a longitudinal study. Recent research among a cohort of French-speaking Caucasian boys living in disadvantaged neighborhoods in Montreal, Canada examined the association between impulsiveness and problem gambling. Impulsiveness is an interesting area of research because pathological gambling is classified in the Diagnostic Statistical Manual (DSM) as an impulse control disorder. Impulsiveness was measured in two ways when the boys were 13 years old: 1) self-reported impulsiveness using the Eysenck Impulsiveness Scale, and 2) teacher assessment of boys’ impulsiveness. When the boys reached 17 years of age, the South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS) was administered with a 12-month time frame. In addition, frequency of 11 different gambling activities over the past 12 months was assessed. A frequency/diversity score was computed by adding the frequency scores. “High problem gamblers” were defined as those scoring 3 or more on the SOGS, “low problem gamblers” scored 1 or 2 on the SOGS, “recreational gamblers” scored 0 on the SOGS but 1 or more on the frequency/diversity scale, and “non-gamblers” scored 0 on both scales. The results revealed an association between both impulsiveness scores (self-report and teacher assessment) and gambling group membership; there was a linear trend for impulsiveness scores to increase as gambling severity increased. Researchers asked the boys one gambling question when they were 13 (“Over the past 12 months, how often did you gamble for money with people who are not family members?”). Analysis revealed no interaction between impulsiveness and gambling activity at the age of 13. This study supports the idea that early impulsiveness is associated with later problem gambling. Additional longitudinal studies are necessary to explore other factors associated with pathological gambling whose temporal relationship is unclear.

Source:

Vitaro, F., Arseneault, L., & Tremblay, R.E. (1997). Dispositional predictors of problem gambling in male adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry, 154(12), 1769-1770.

This public education project is funded, in part, by The Andrews Foundation.

This fax may be copied without permission. Please cite The WAGER as the source.

For more information contact the Massachusetts Council on Compulsive Gambling,

190 High Street, Suite 6, Boston, MA 02110, U.S.